Version Control with Git

Modern Plain Text Social Science: Week 06

October 7, 2024

Plain Text Credo Again

Keep Backups

You Need Backups That Are

- Secure

- Automated

- Redundant

- Remote

These are Not Backups

- Your computer

- Your old computer

- An attachment you emailed to yourself

- A USB Drive you updated twice and forget where it is maybe it is in the drawer in the kitchen oh god i hope so please please

Not Nearly Good Enough

These services are good for a lot of things, and some of them are like backups in some ways, but they are also not really backups.

- Google Drive

- Dropbox

- Box

- Git/GitHub

Pay for a Reputable Service

E.g., Backblaze.

If ensuring that you have access to your work in the event your laptop is stolen, dropped, lost, breaks, fails, or has coffee spilled on it is not worth nine bucks a month to you, perhaps reconsider the value of your time, your personal risk tolerance, and your career choices.

- “When it comes to losing your data, the universe tends toward maximum irony. Don’t push it.” — Jamie Zawinski

Remember

- Secure

- Automated

- Redundant

- Remote

Knowing what you did

“To remember everything is a form of madness.”

We need to keep track

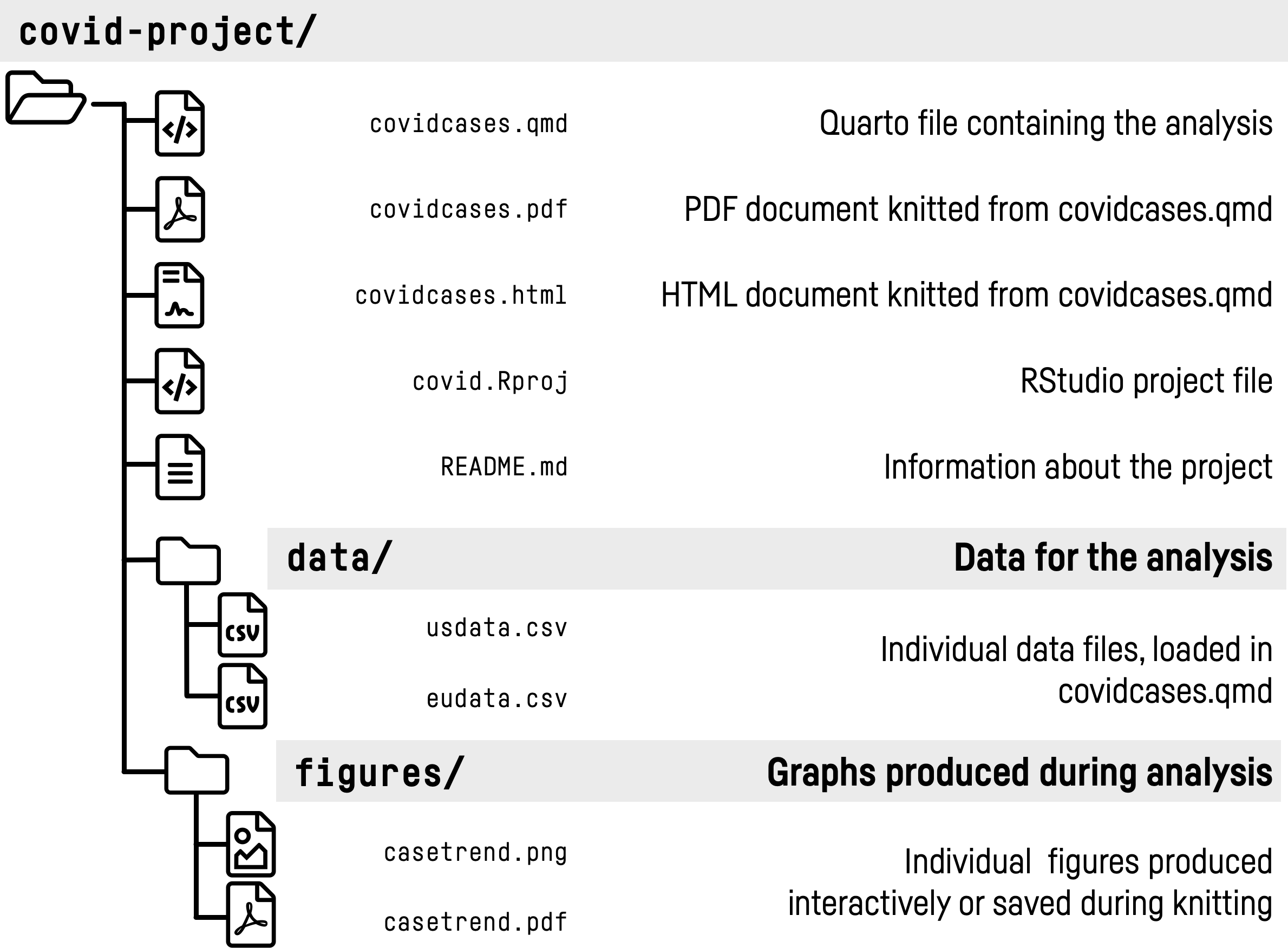

- When you get down to it a “research project” is a folder on your computer that contains a bunch of files and subfolders.

- We need to track things at the level of our project.

- There’s a long history of software that can keep track of how files in projects have changed, and who did things to which files.

- A tool like this is called a Version Control System or a Revision Control System.

- Modern solutions are sometimes called Distributed Version Control Systems because of some additional capabilities they have.

Problems a (D)VCS Solves

- Track changes you make to project files.

- Do this in terms of or at the level of the project as a whole.

- Keep track of who made which changes to a file and when.

- Jump back to any previous point to see the state of the project then.

- Manage new content or revisions by breaking them into branches or offshoots that can also be tracked.

- Merge these offshoots and branches back into the main line of the project as needed.

- Figure out when a change that breaks something later got introduced earlier.

Sidenote: a VCS is a DAG

You are going to see a lot of diagrams like this in papers, talks, and seminars you’re required to take.

Sidenote: a VCS is a DAG

Sidenote: a VCS is a DAG

Git

- Git is the industry-standard DVCS. There are others, but it’s the main one.

- It’s very powerful.

- It’s used to run the software development projects of gigantic corporations that must coordinate huge projects with contributions by hundreds or thousands of developers.

- It makes professionals and amateurs alike cry on the regular. But there are a bunch of cry-minimizing ways of using and interacting with it.

Git

- We can start by using a very small fraction of git’s functionality. This can be enough to get by for a long time and is way better than nothing.

- As projects get more complex—with multiple contributors to multiple tasks—then git offers a way of working that can help bring order to this complexity, and leave a record in its wake.

- Again, Git is the standard for basically everything that gets done in the world of technical computing. All software development is done in this way, or something functionally the same as it.

Git as a Logbook

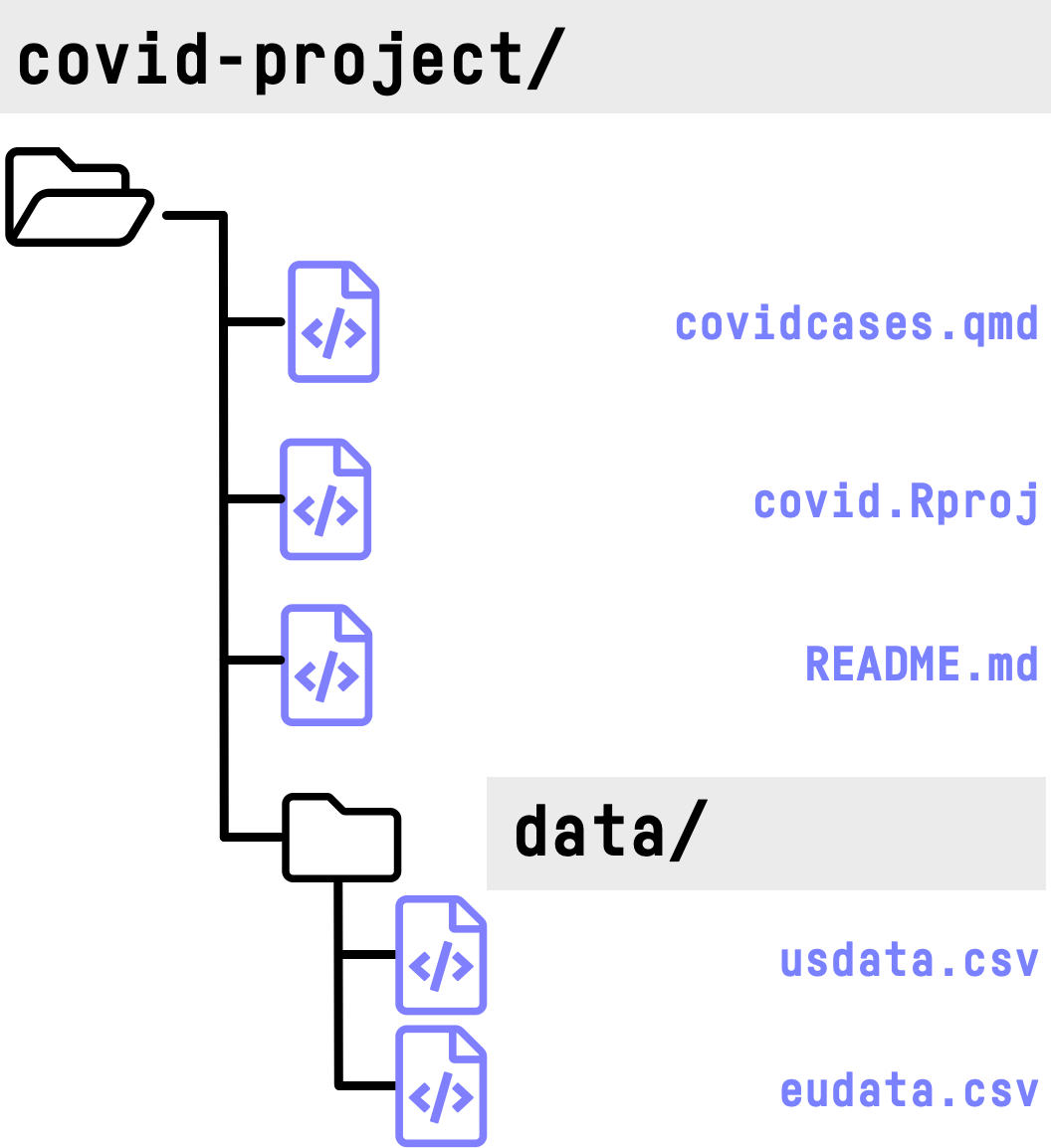

Our sample project

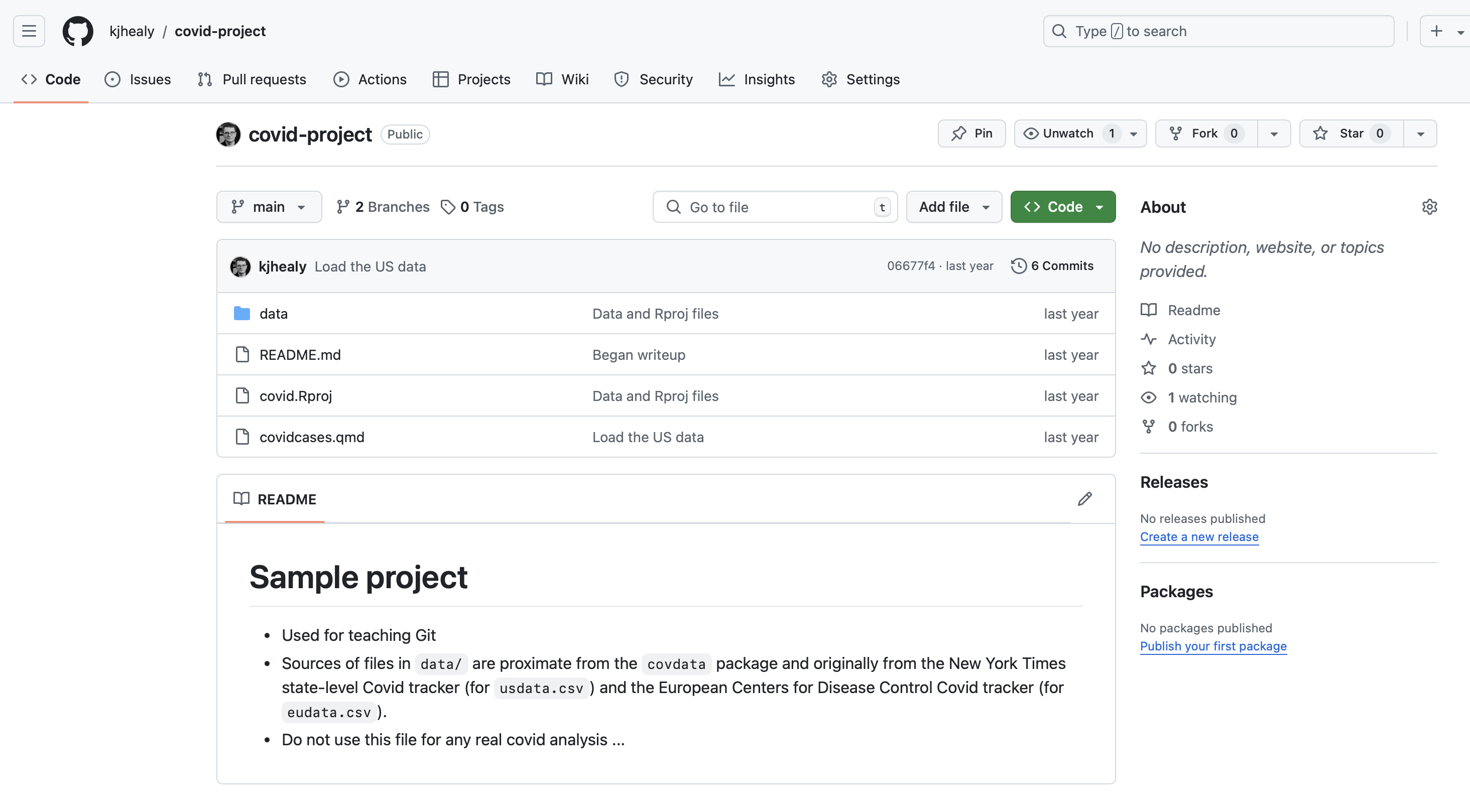

- This project can be found at https://github.com/kjhealy/covid-project

What must we track?

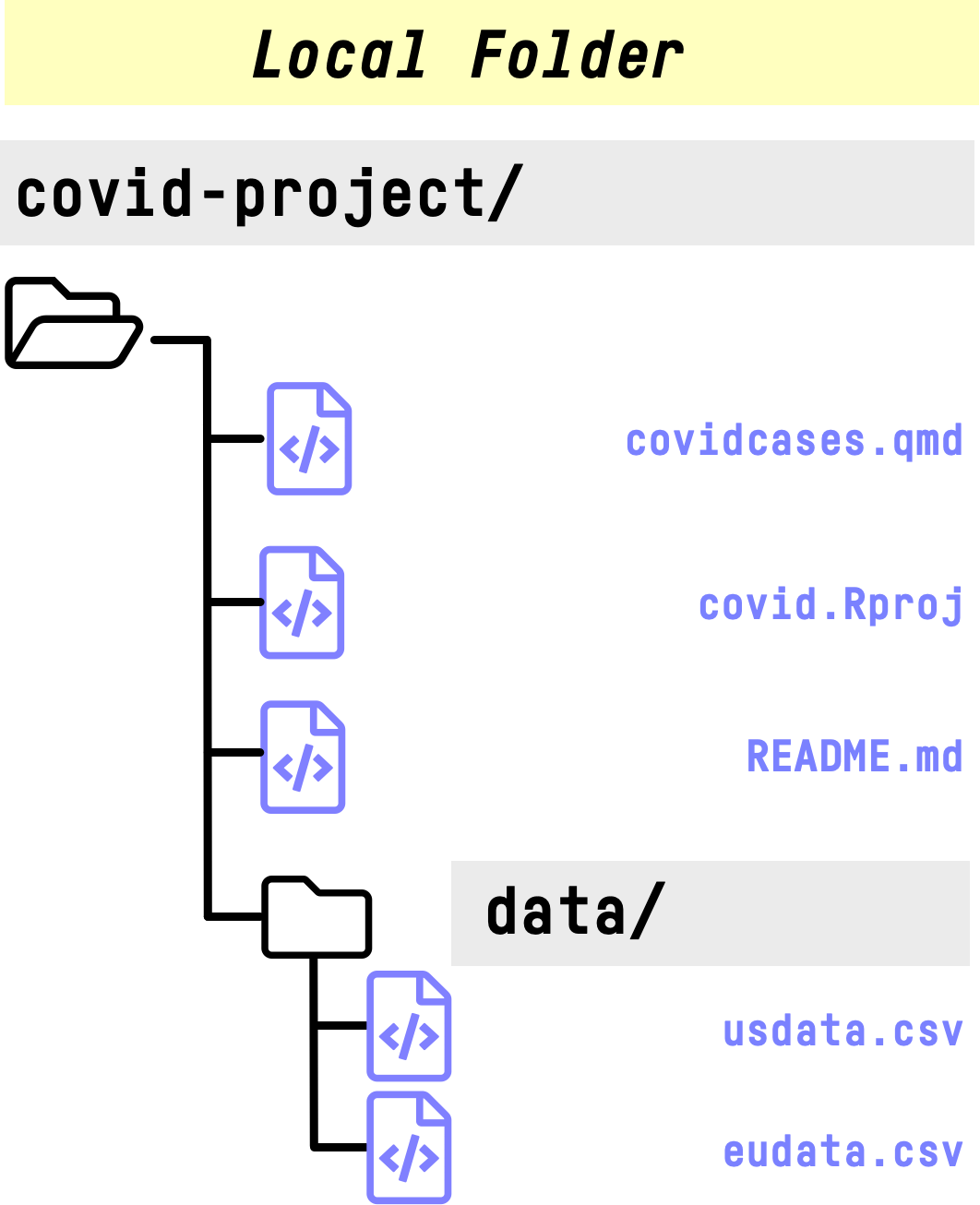

This is our local folder

- Lives on our laptop.

- Just a regular folder with files.

- At any moment will have stuff we need to track, and outputs and other things we don’t need to track.

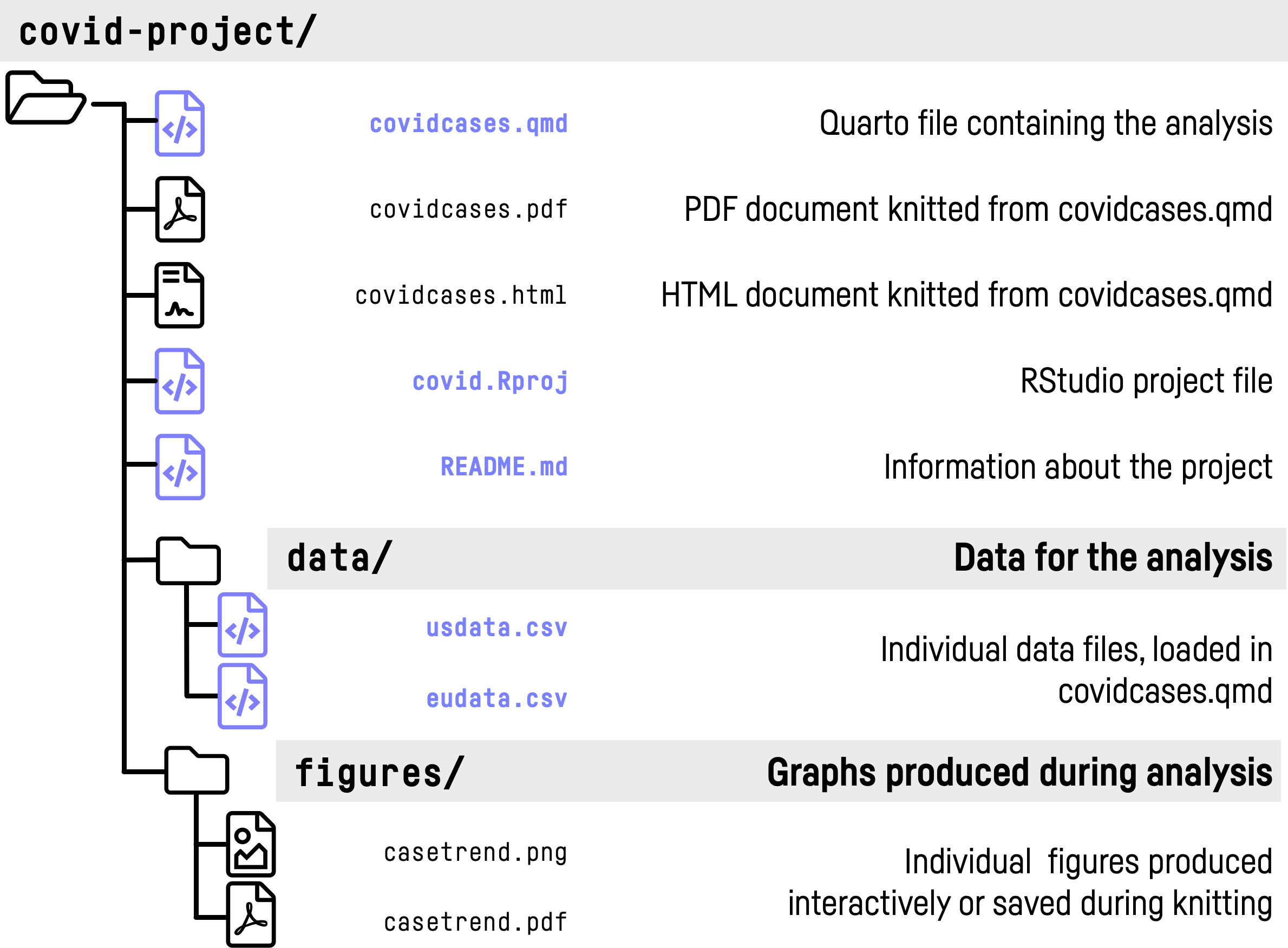

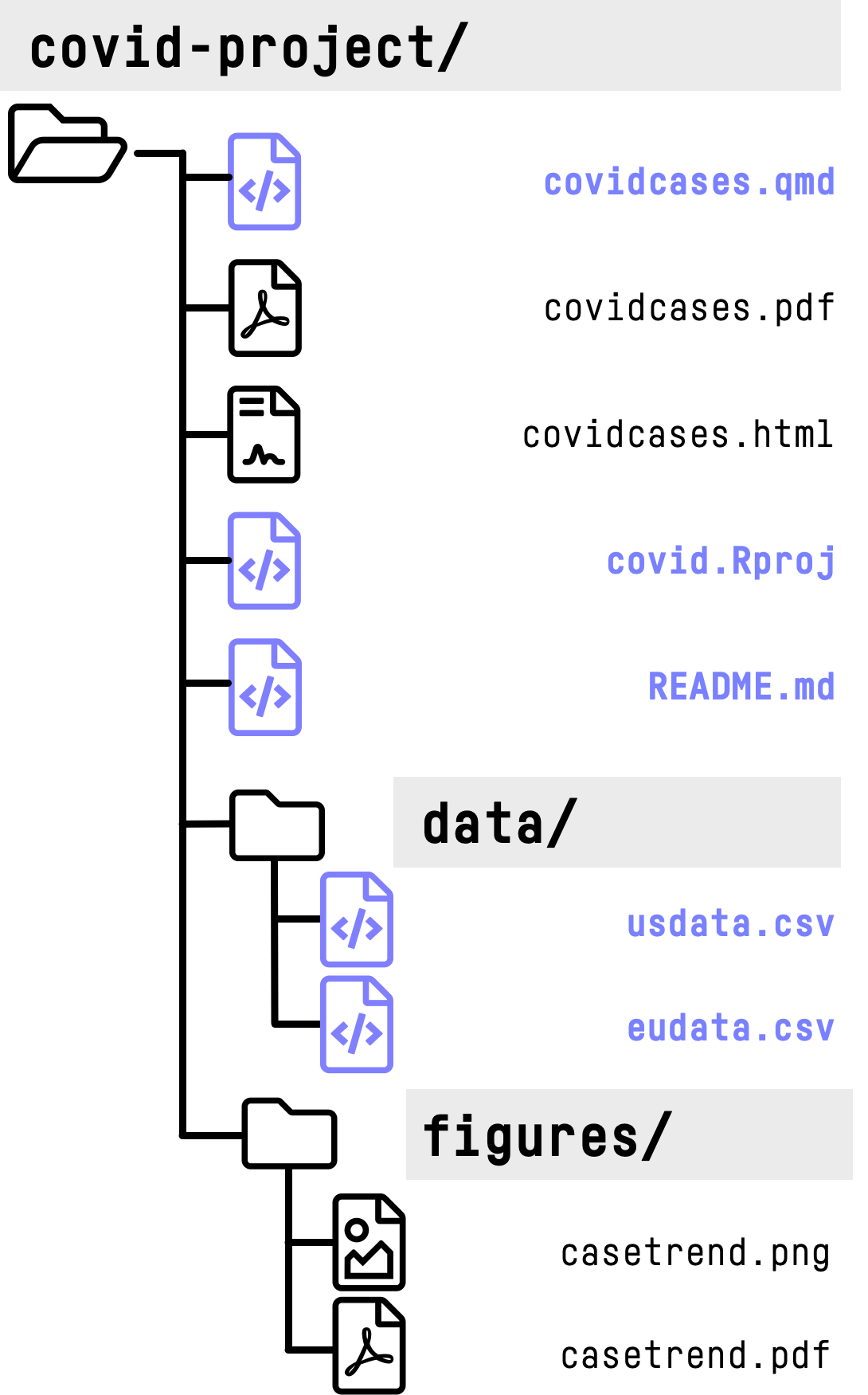

This is what we need to track

- Sidenote: It’s true that, even though they are generated by code and not ‘real’, for figures and tables (and final outputs like papers) we will often want to know which version of the code and data they were produced with.

- We’ll come back to this in more detail later on. We can write an R function to stamp a version identifier on the output.

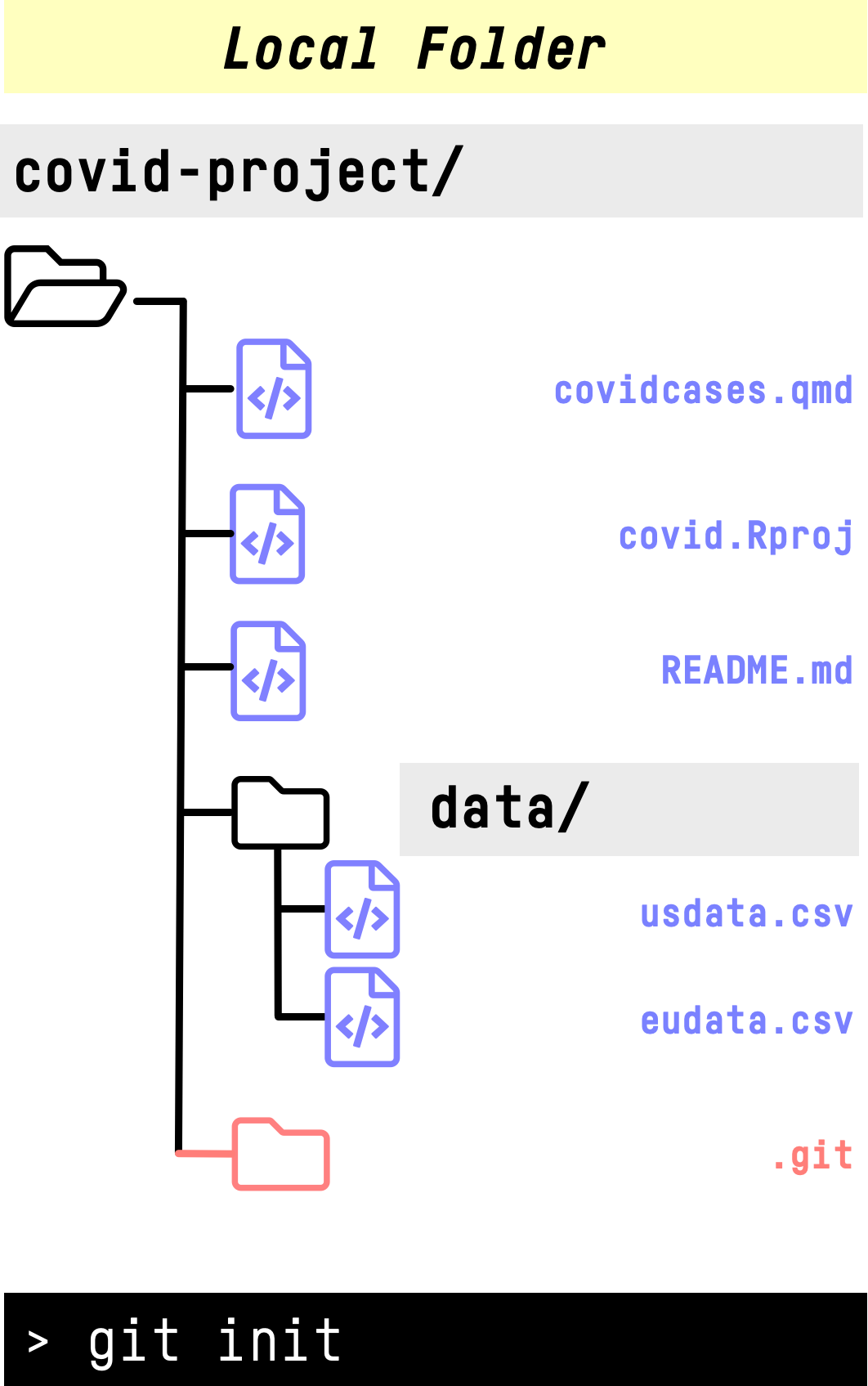

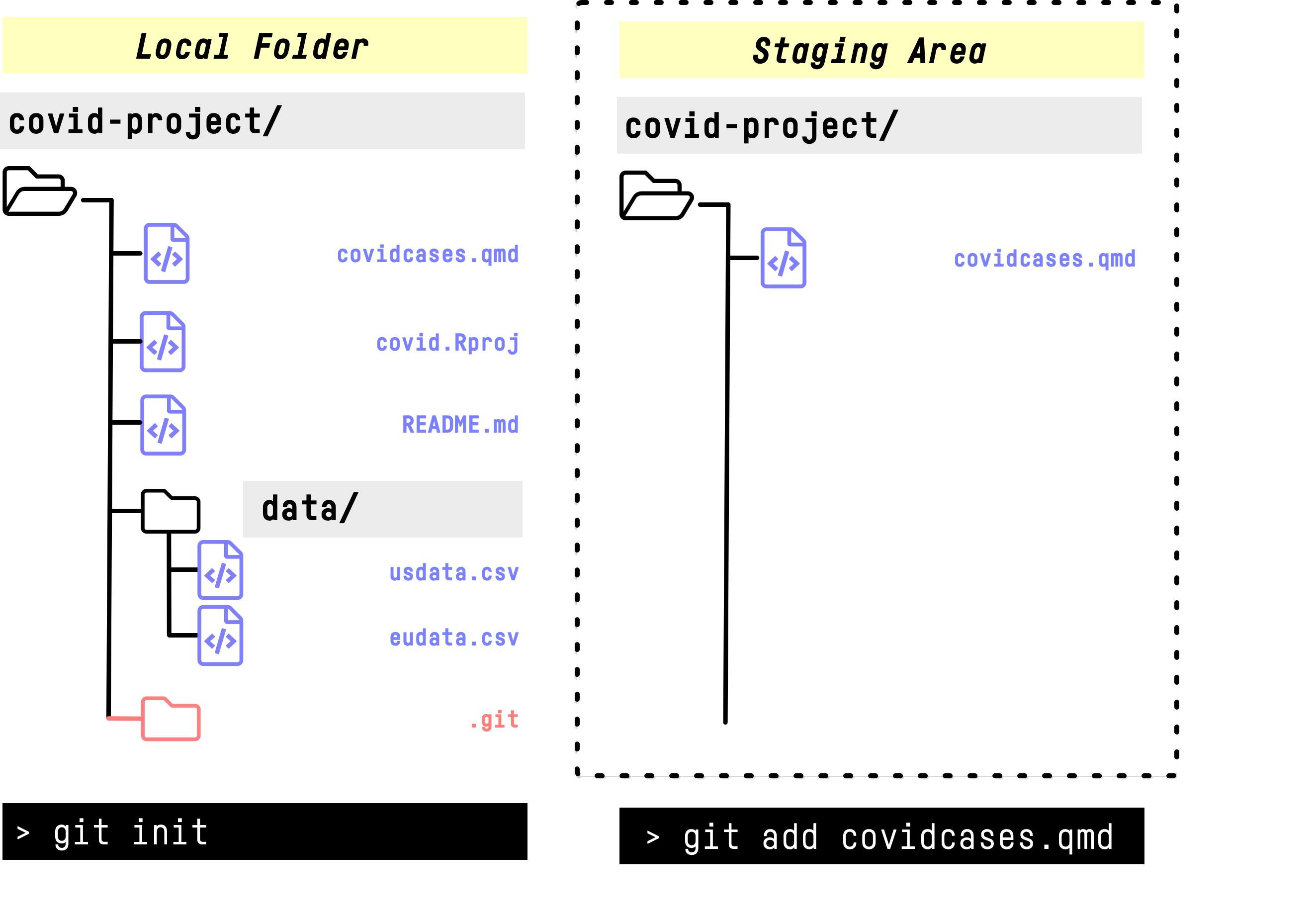

Initialise a repository

- Our record of changes and edits to files is called a repository or repo.

- It has to exist somewhere.

- With

git, it exists as a “hidden” folder that has a record of all the changes. It’s stored inside the project. To create it, we initialise the repo.

Initialise a repository

- The

.gitfolder is “hidden” because its name begins with a dot.

- Inside it contains its own file and folder hierarchy for keeping track of changes to our project.

- Now we need to tell git what to track.

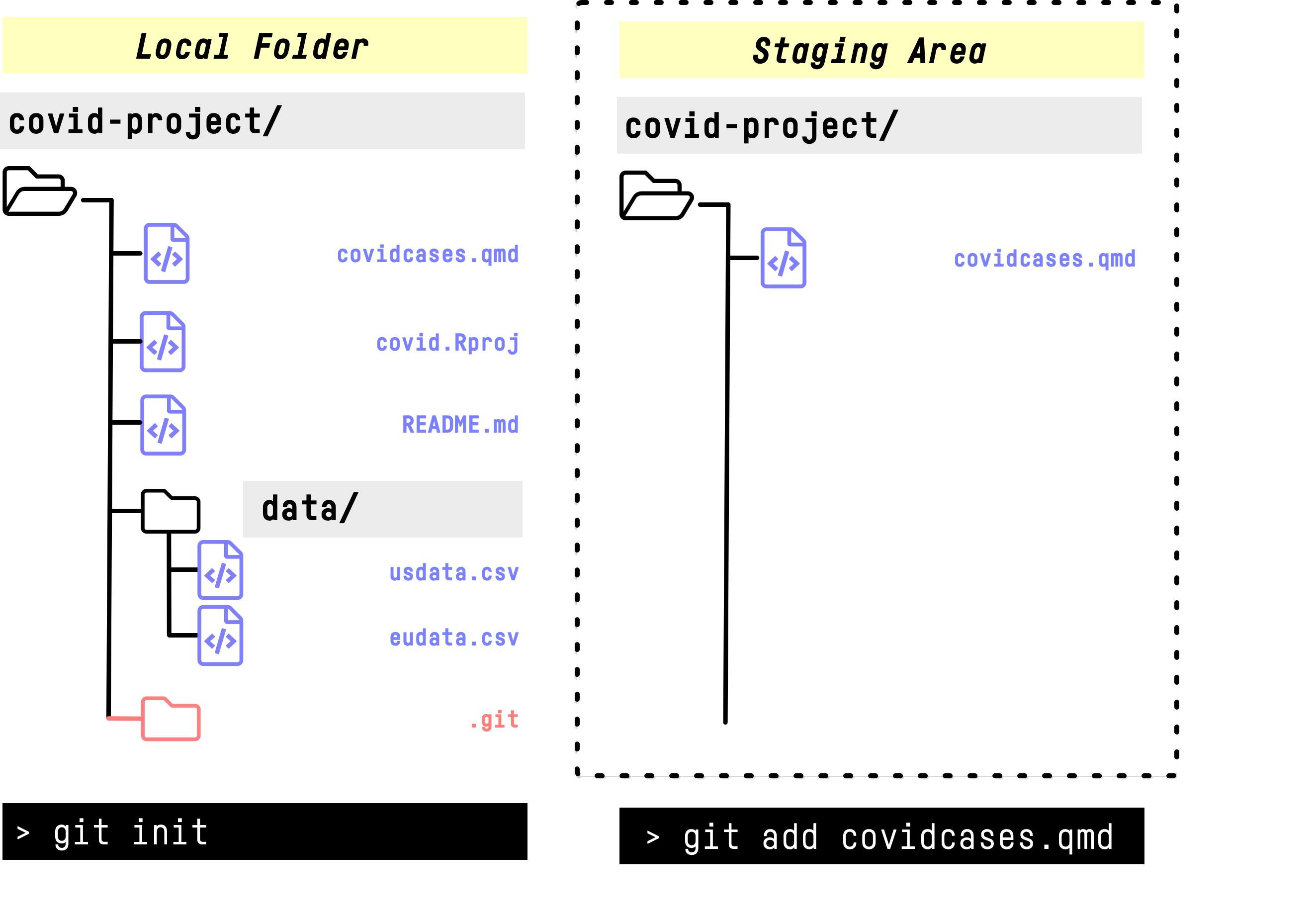

Staging a file

- The first step is to “stage” a file with the command

git add <filename> - This adds the file to an index of things git is going to manage.

- Git keeps this index inside the

.gitfolder.

Staging a file

- No changes are recorded at this point.

- Nothing changes in our local folder.

- We’ve just added a file to a list of items to be tracked.

- As the name suggests, conceptually the staging area is preparatory.

- … Preparatory to what?

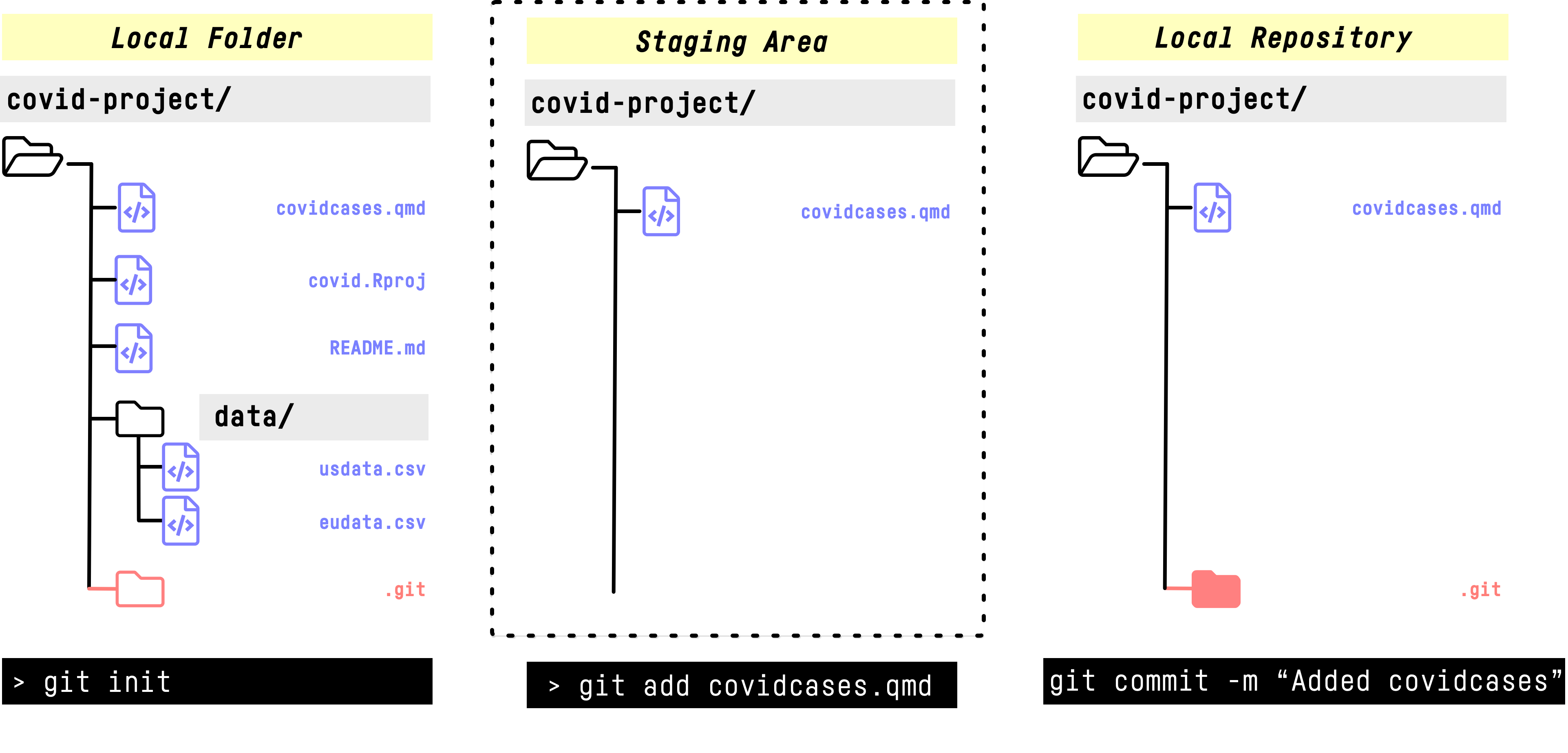

Committing a file

- Committing a file makes a record of it in our local repository.

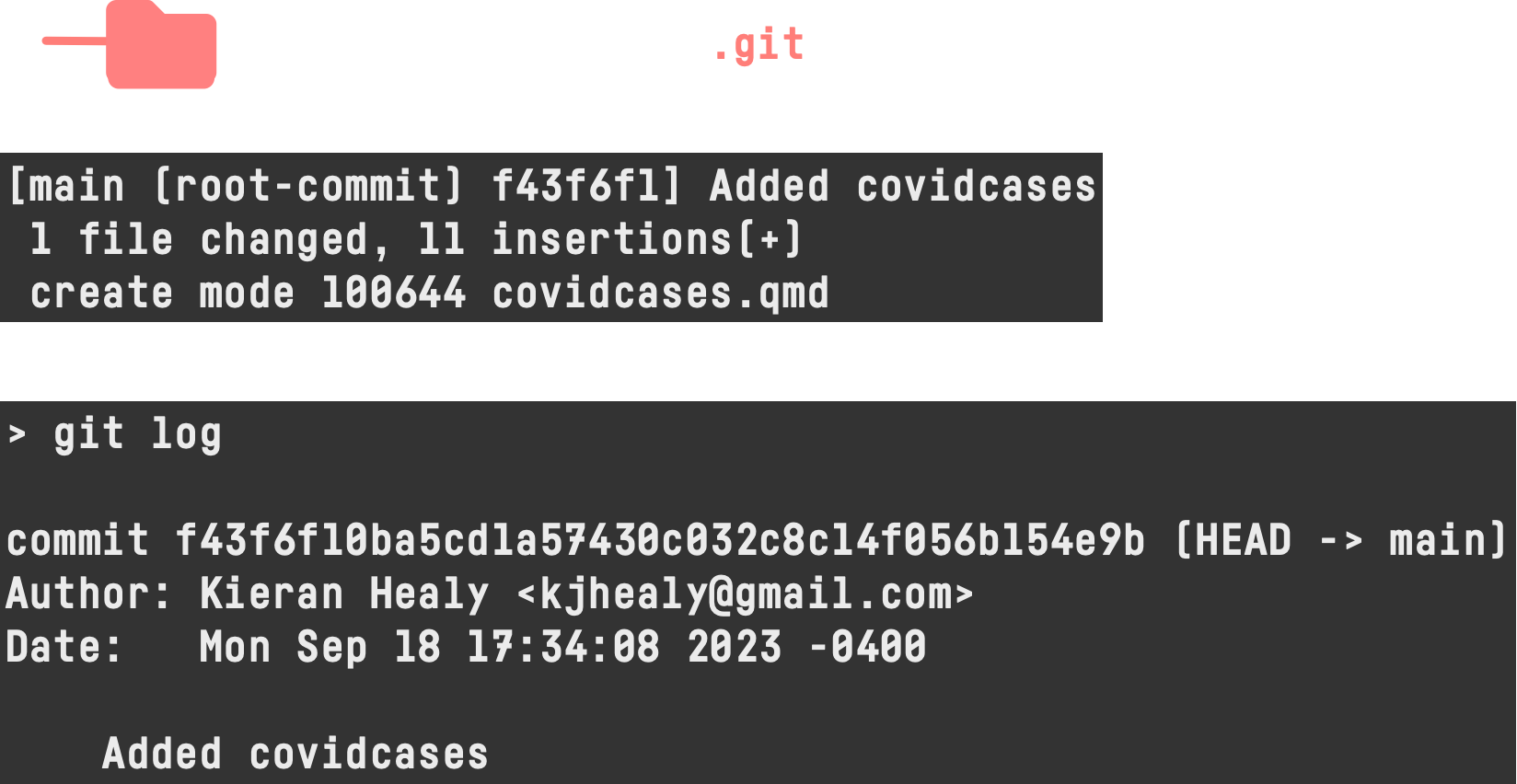

Committing a file

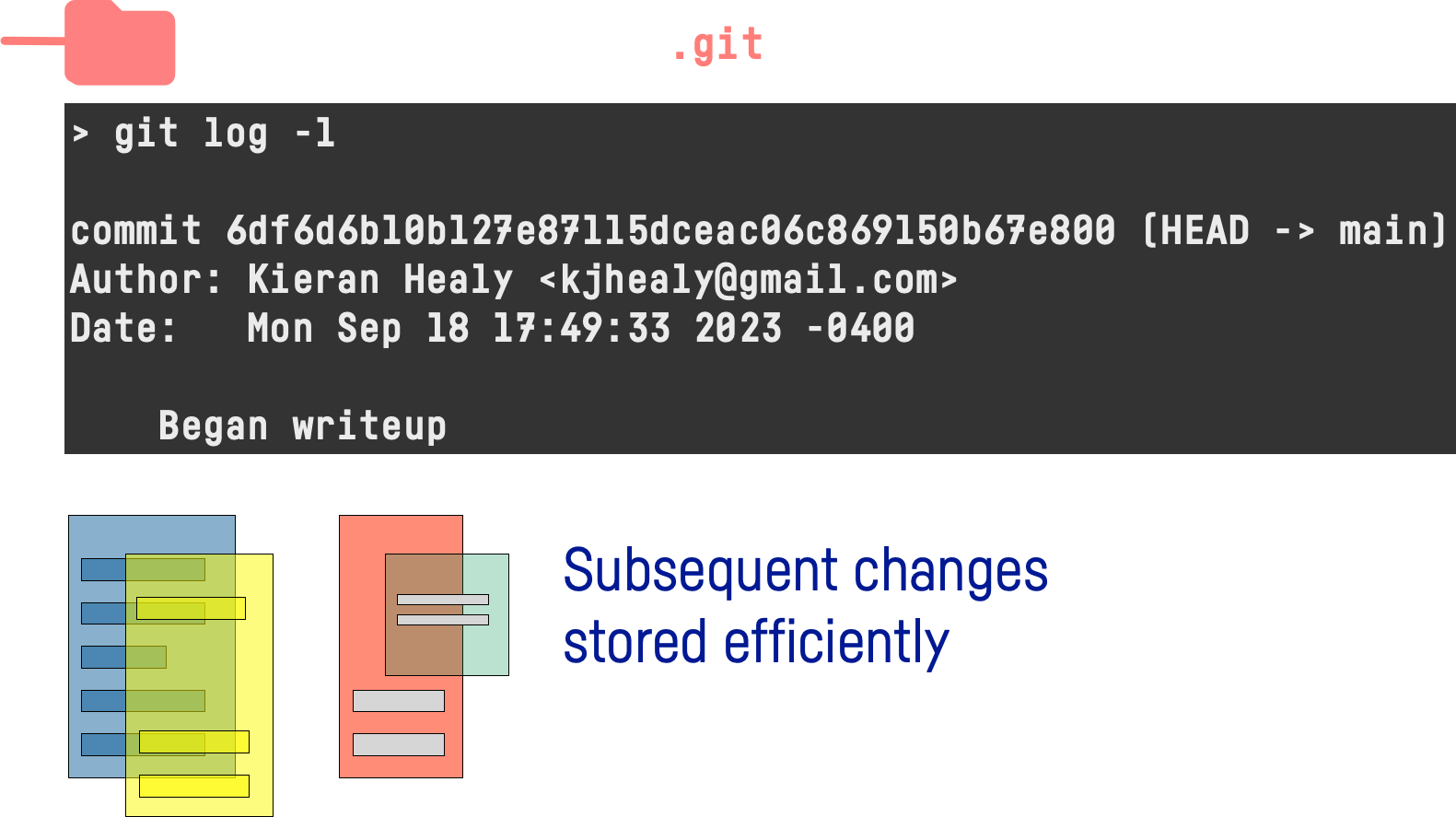

- The 64-bit hexadecimal number is an SHA Hash.

- It’s derived from the file(s) being committed and it uniquely identifies the changes associated with that commit.

- The message added with

-mis for our benefit. It should be terse and informative about what’s new, fixed, or changed in the commit.

Committing a file

- Inside the

.gitfolder, a compressed version of the file is created.

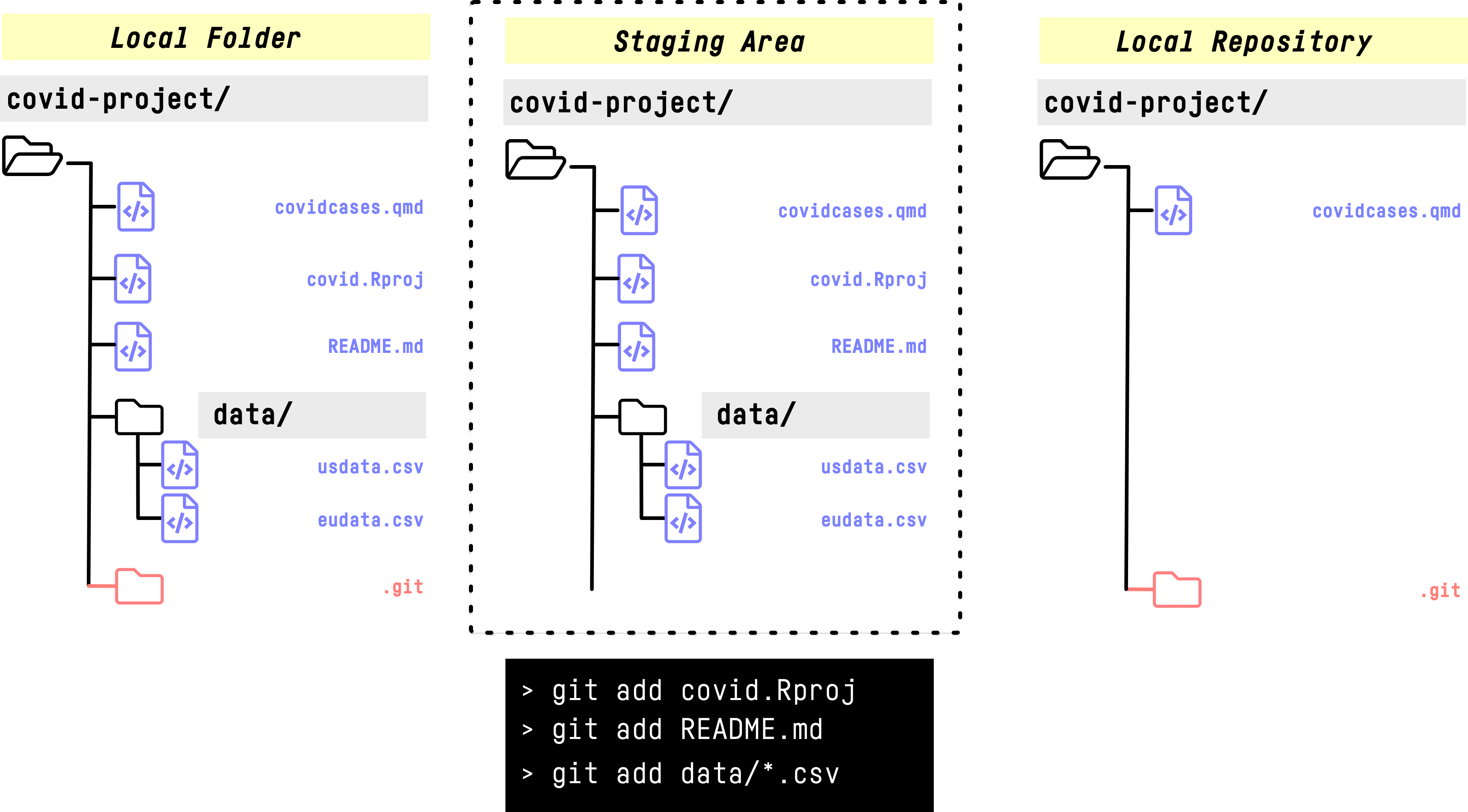

Staging several files …

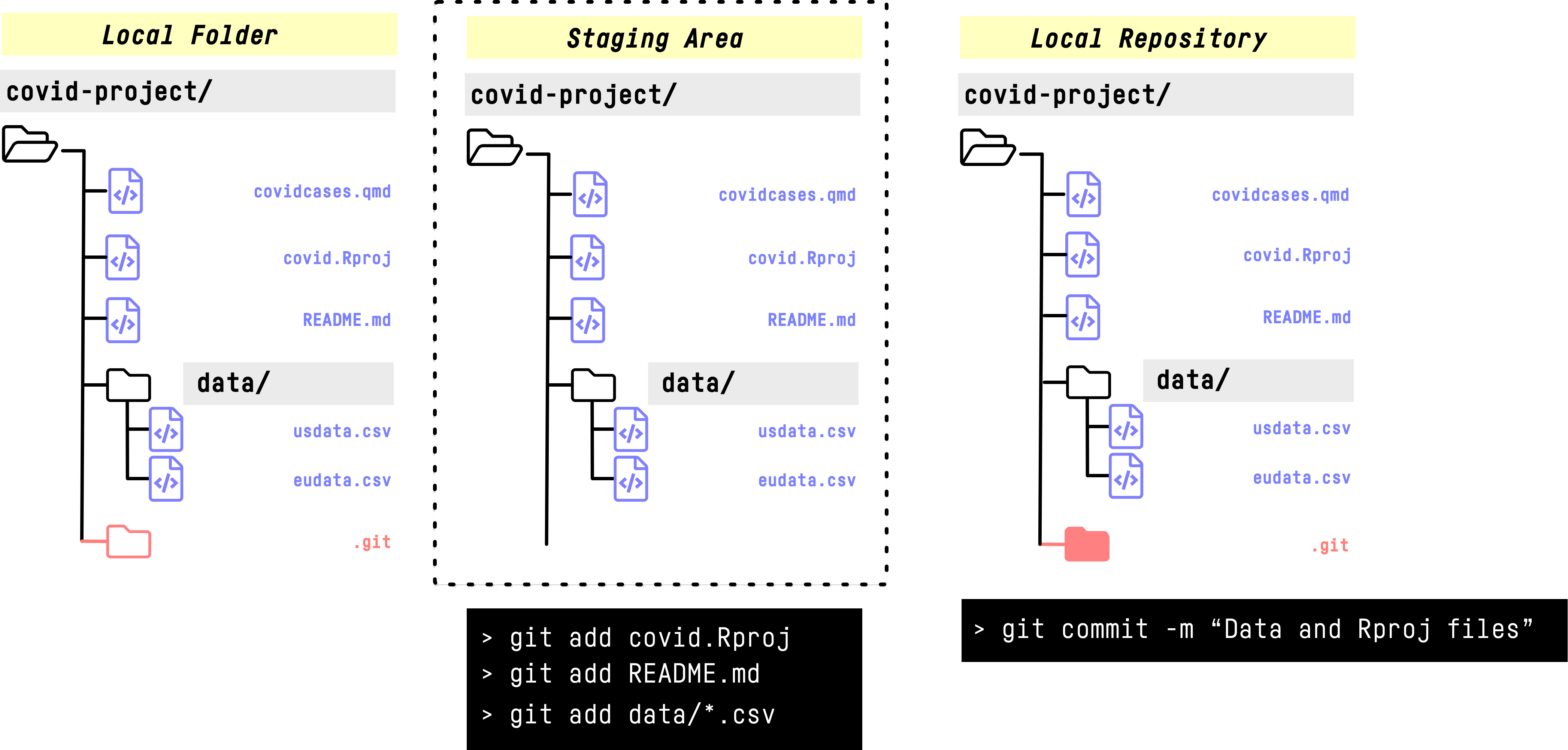

… and committing them

Committing several files

Remember …

- The Local Folder is our project as we (and the file system) can see it.

- The Local Repository lives inside the special

.gitfolder that sits at the root of our project. Conceptually we think of it as its own separate thing that git is managing for us. - We can move files and folders in and out of our local folder, edit them, and so on, just as we normally would.

- But for git to track and manage any of these files or changes to them we need to add and commit them to the local repository.

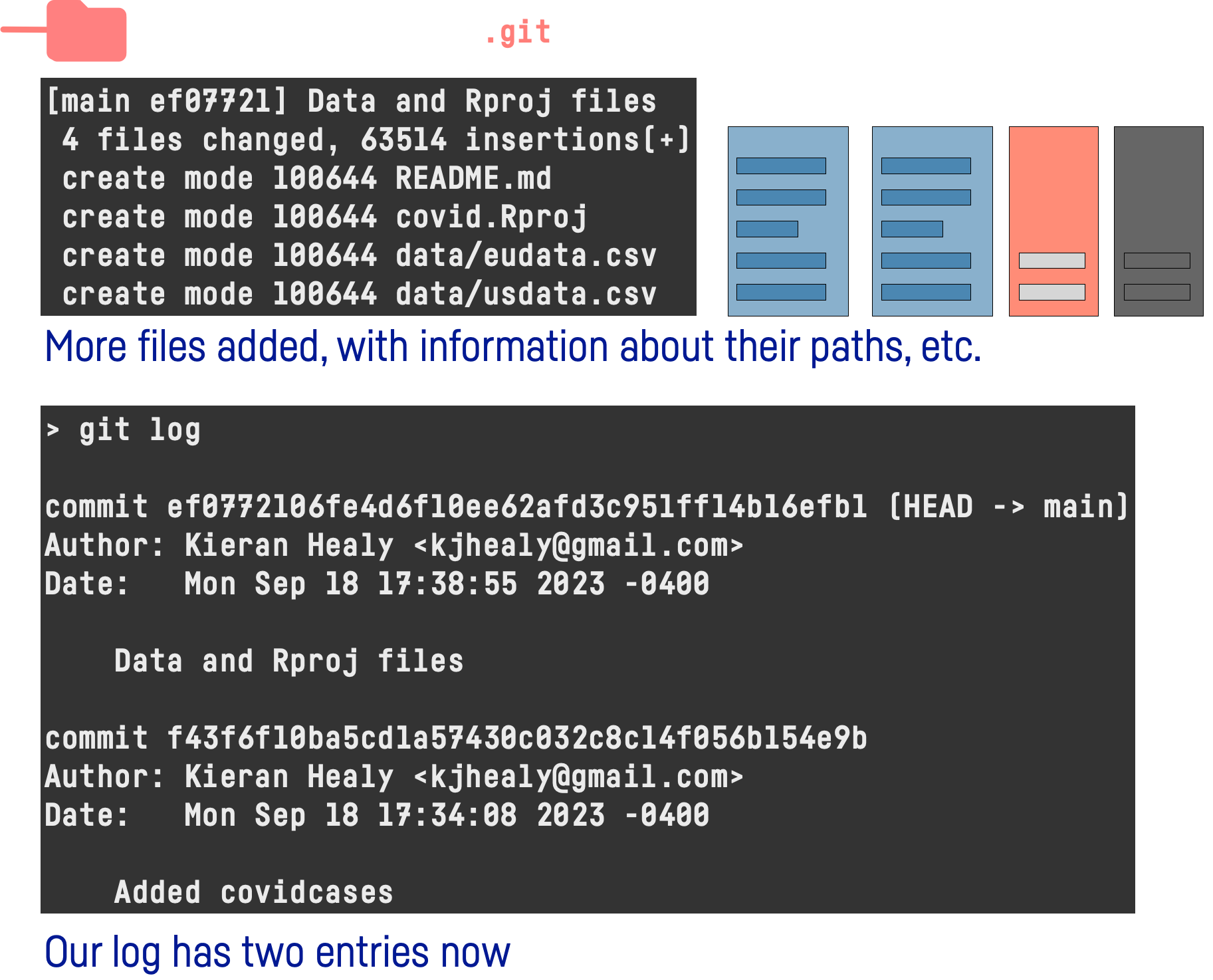

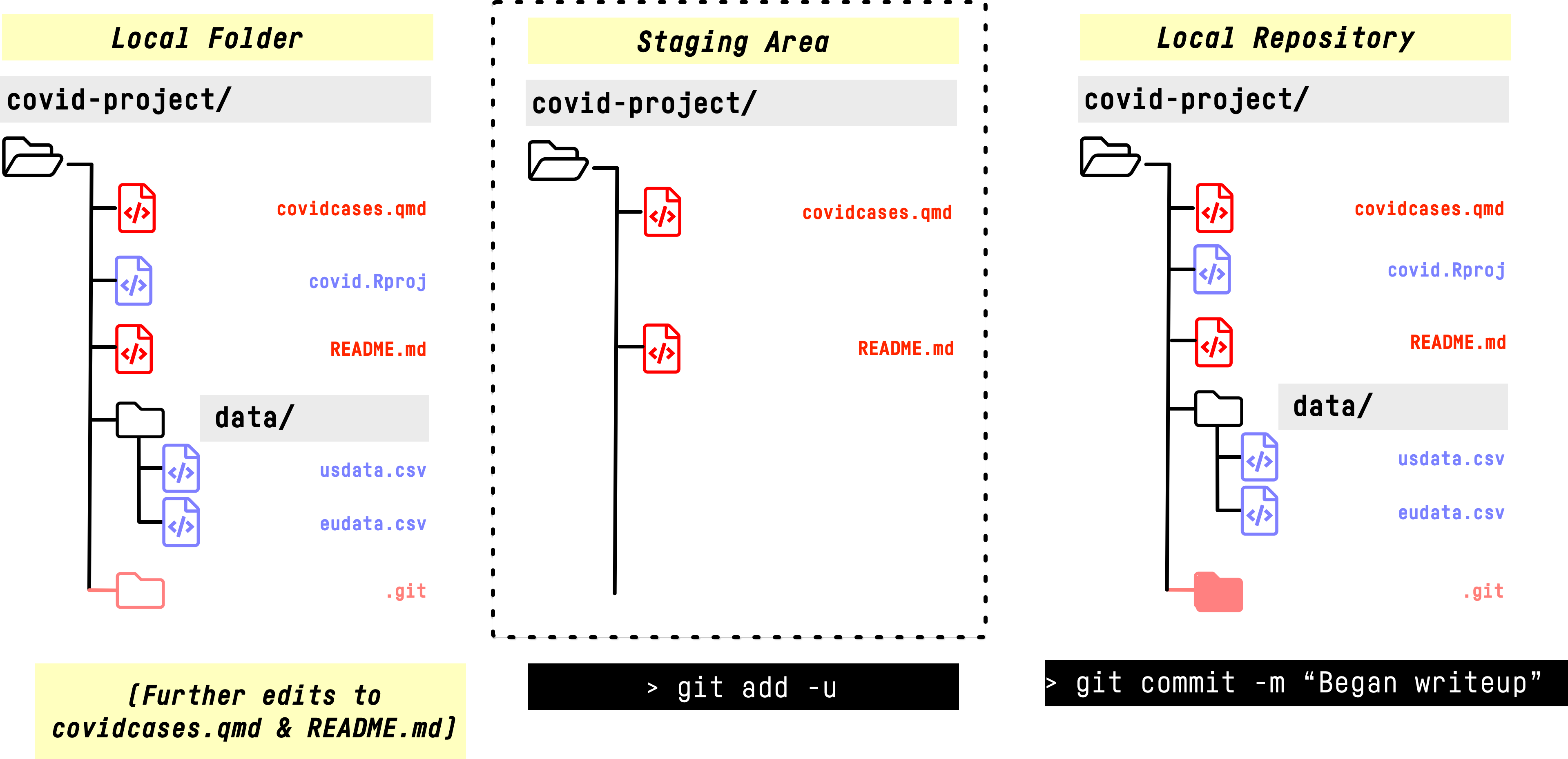

Editing and committing

Editing and committing

Storing the changes

Remember (again) …

- The Local Folder is our project as we (and the file system) can see it.

- The Local Repository lives inside the special

.gitfolder that sits at the root of our project. Conceptually we think of it as its own separate thing that git is managing for us. - We can move files and folders in and out of our local folder, edit them, and so on, just as we normally would.

- But for git to track and manage any of these files or changes to them we need to add and commit them to the local repository.

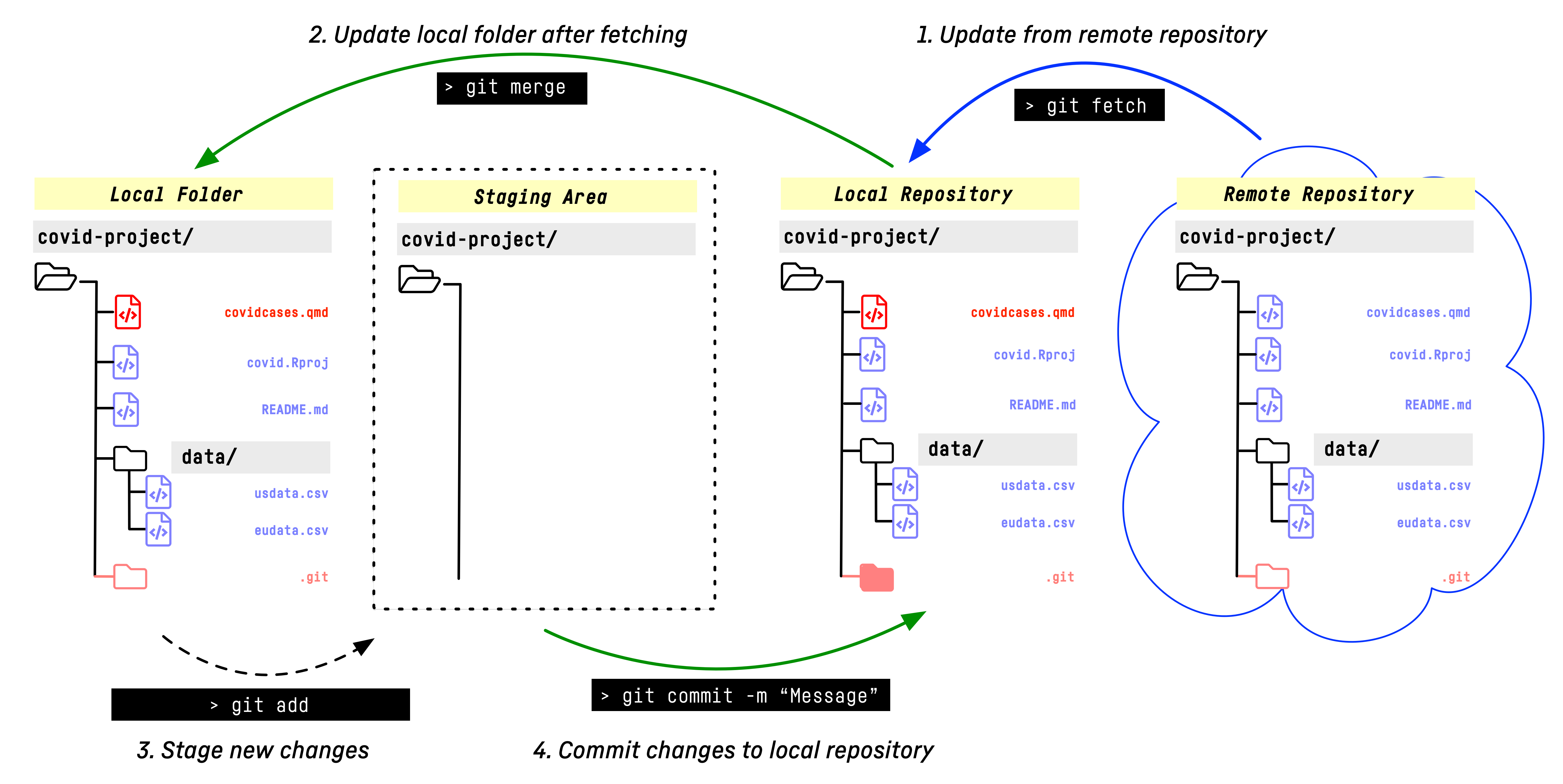

Git as a Log Book

- Working this way, we treat git as managing the files we want to track.

- Physically these changes are managed in the

.gitfolder inside the project. Again, think of it as a separate entity, the local repository. - Every time we decide to record changes to a tracked file in the project we do

git add <filename>andgit commit -m "Message" - We write

git add -uto stage any changes to every already-tracked file. - Newly-created files that we want to stage and commit are not picked up by

git add -u - They must be added by name, either one at a time or with shell-style paths and globs (wildcards).

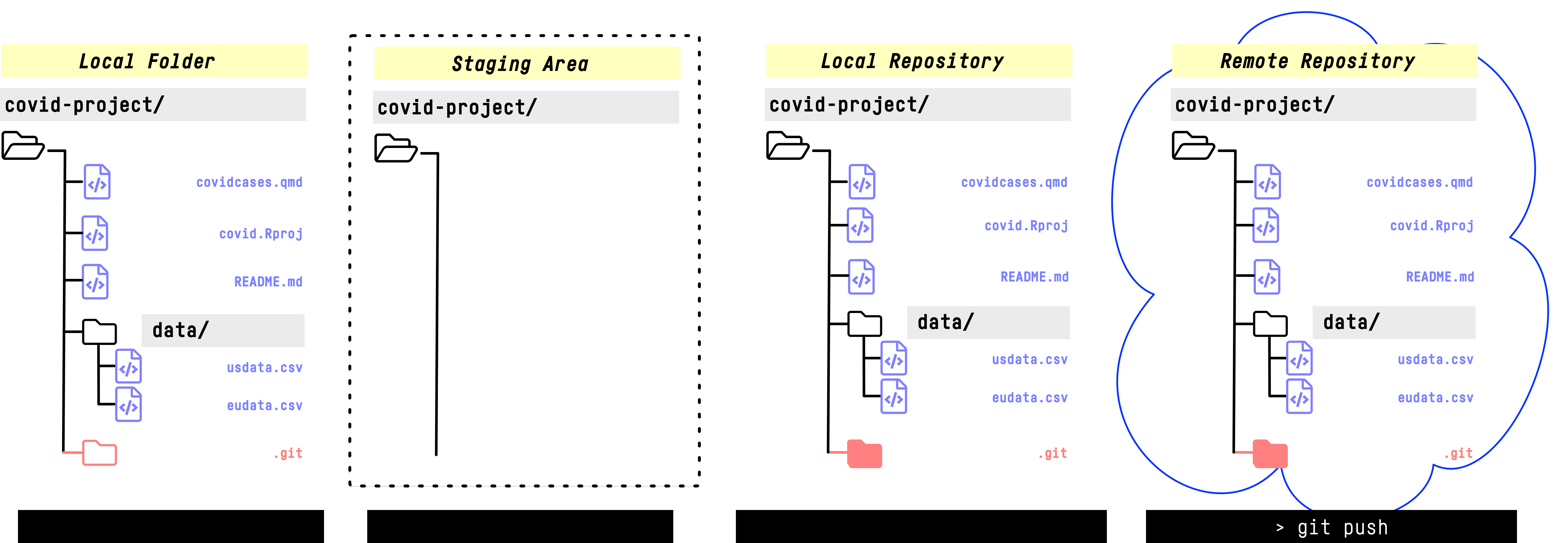

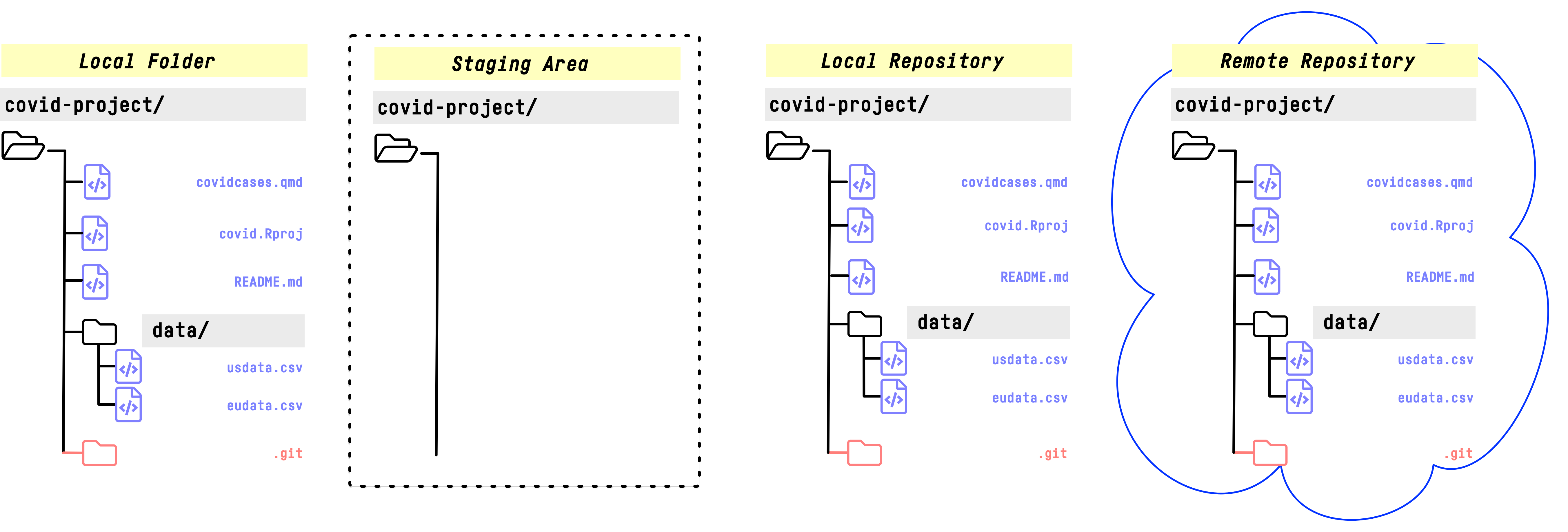

GitHub

Keeping a remote Log

- We have a local repository, but …

- We can also keep copies of it wherever we like.

- In the Cloud, for example …

There’s no such thing as the Cloud

It’s just someone else’s computer

Keeping a remote copy

- We proceed as before but then

pushchanges to GitHub or wherever our remote repository is located.

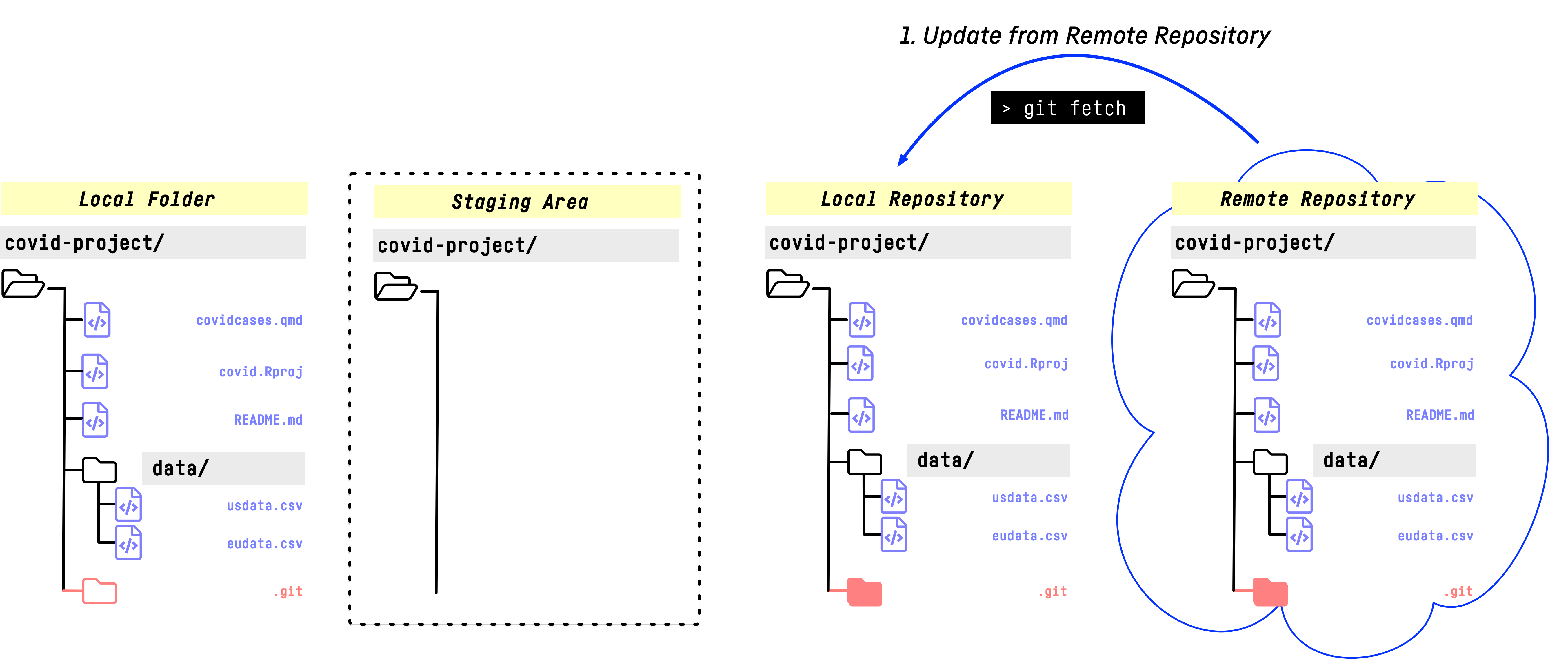

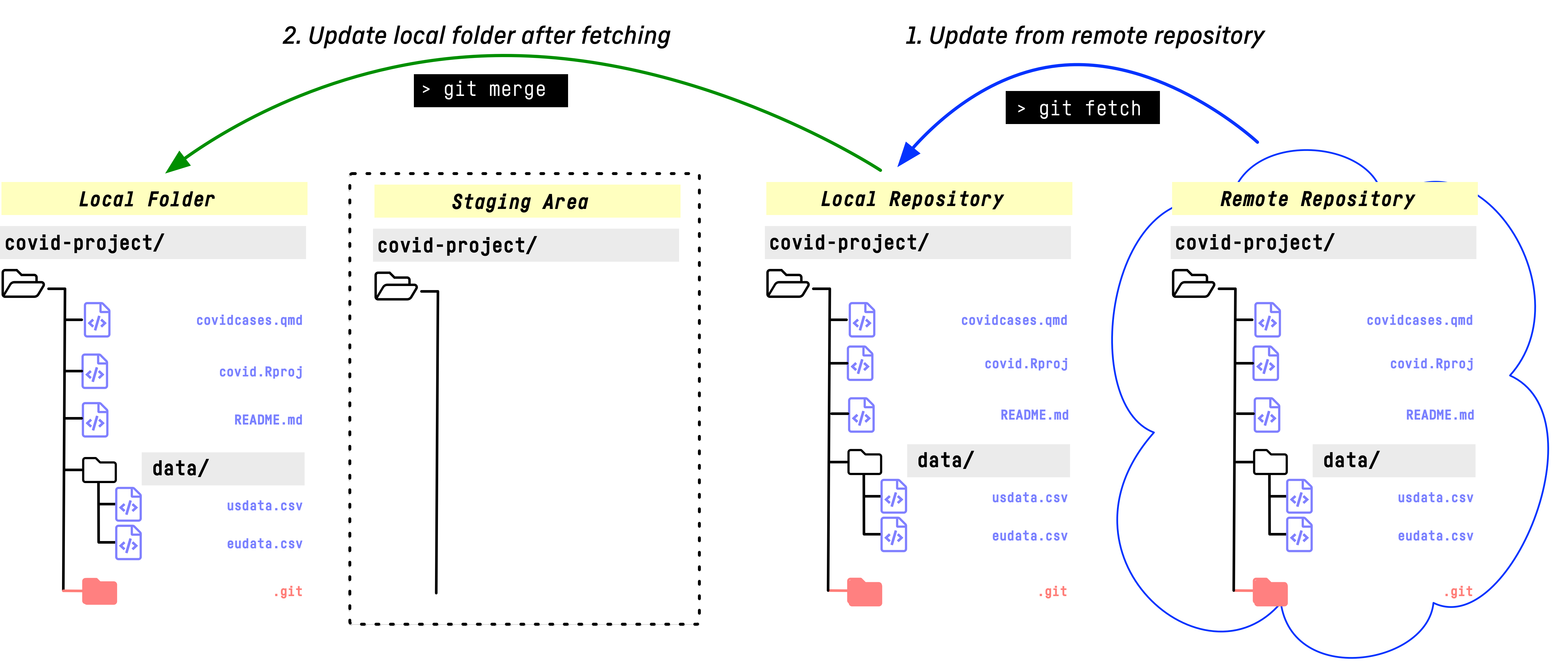

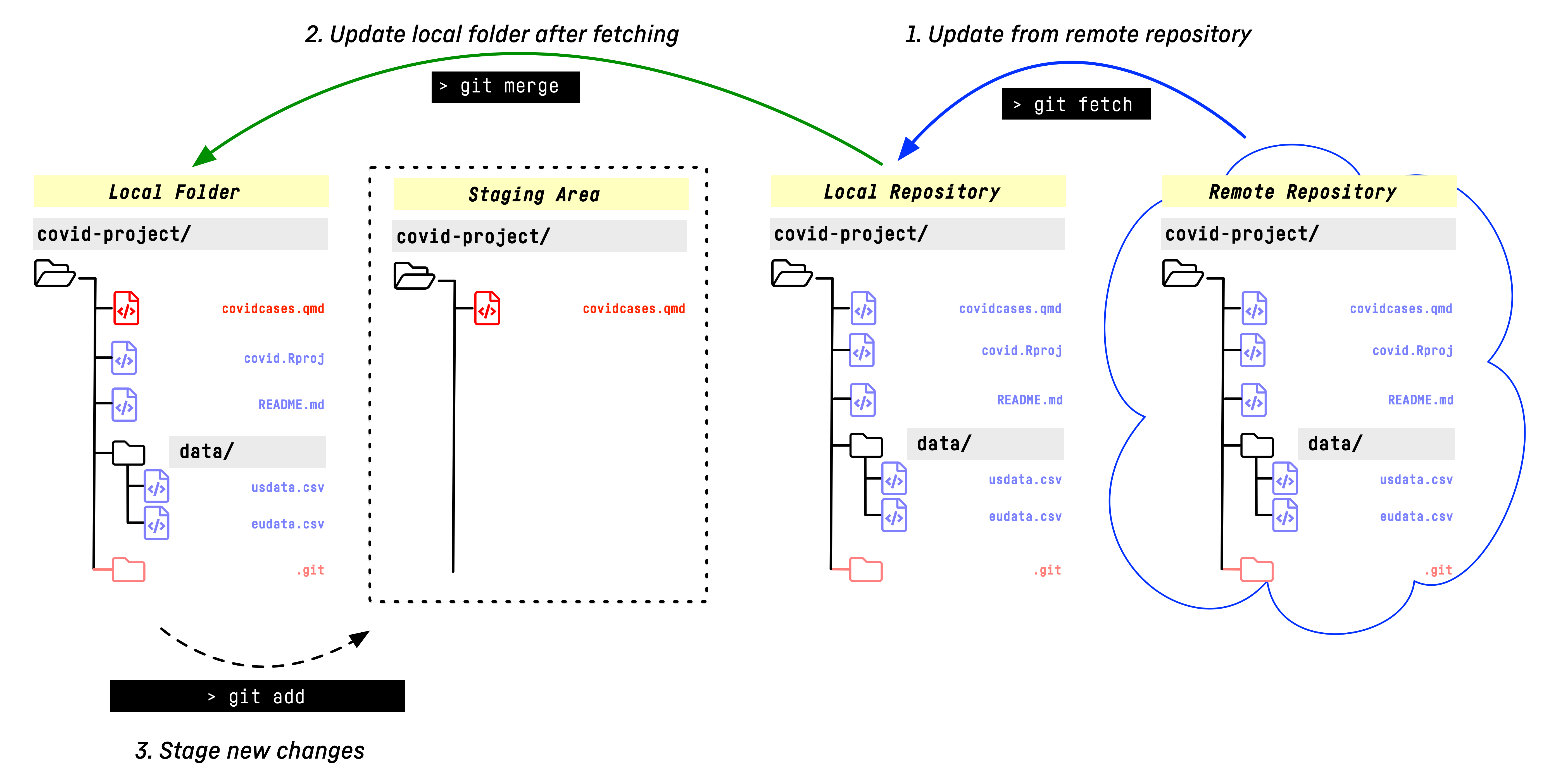

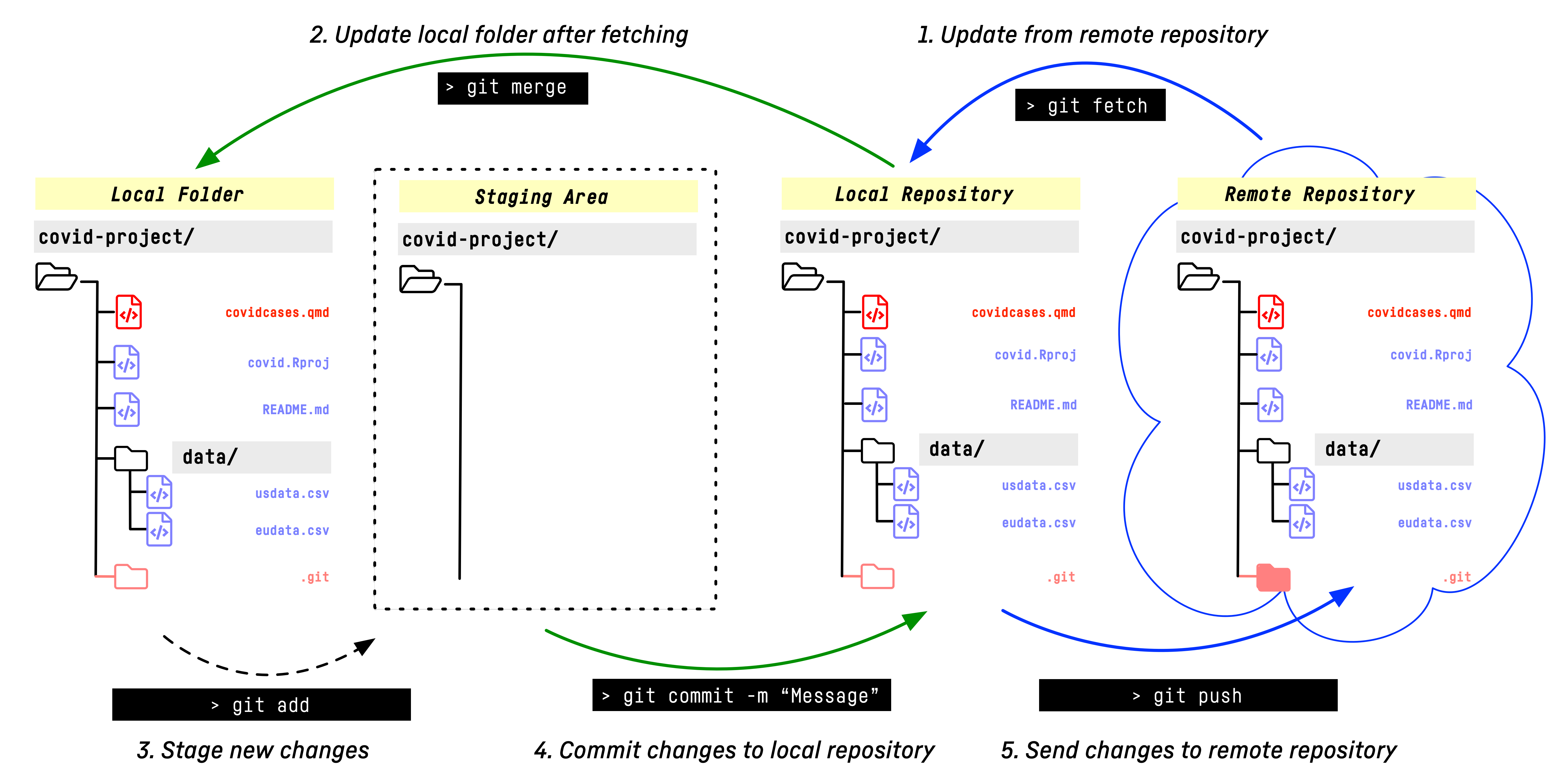

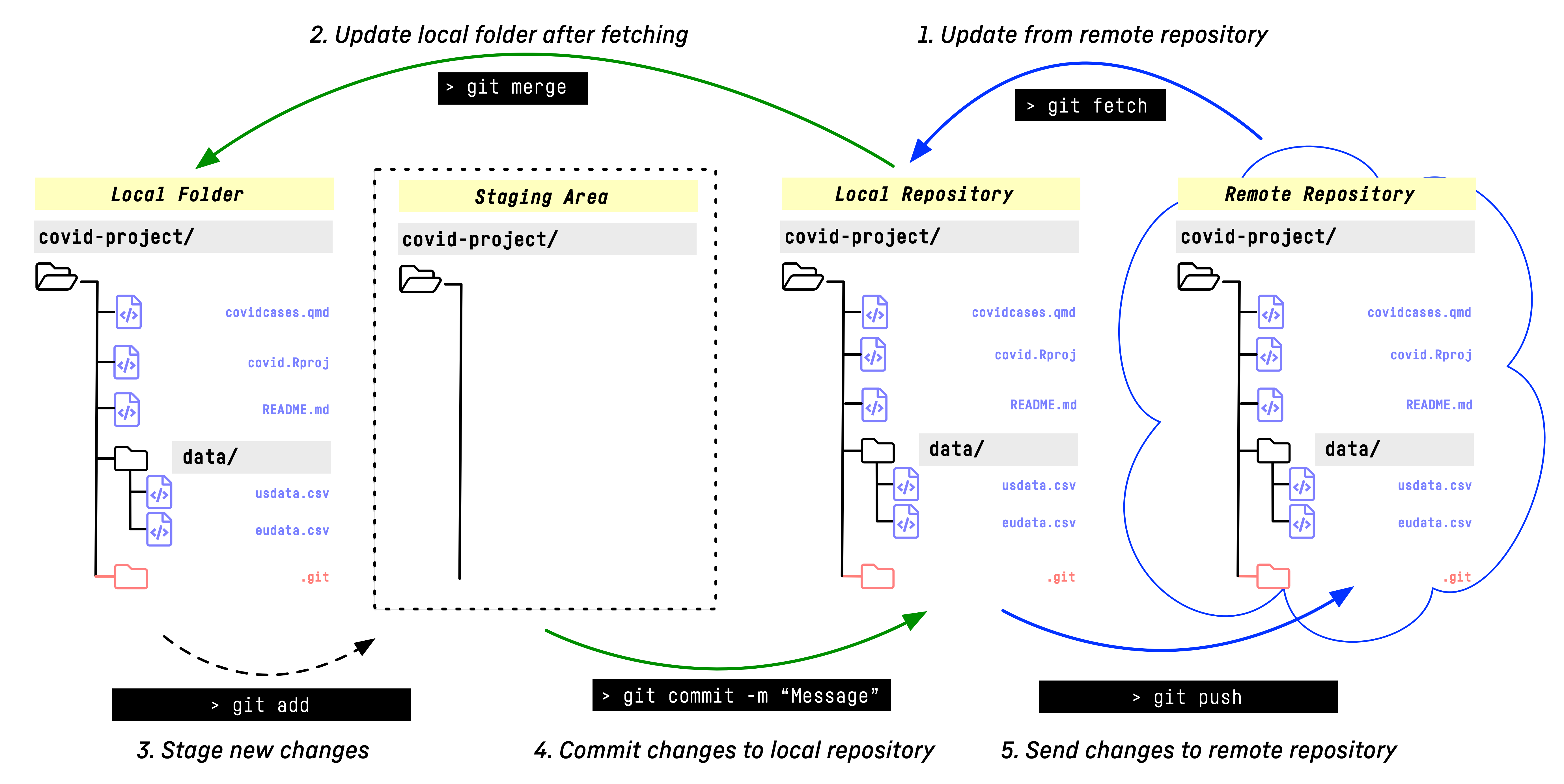

Workflow: GitHub Round Trip

- You should already have a GitHub account set up thanks to Happy Git with R

Workflow: GitHub Round Trip

Workflow: GitHub Round Trip

Workflow: GitHub Round Trip

Workflow: GitHub Round Trip

Workflow: GitHub Round Trip

Workflow: GitHub Round Trip

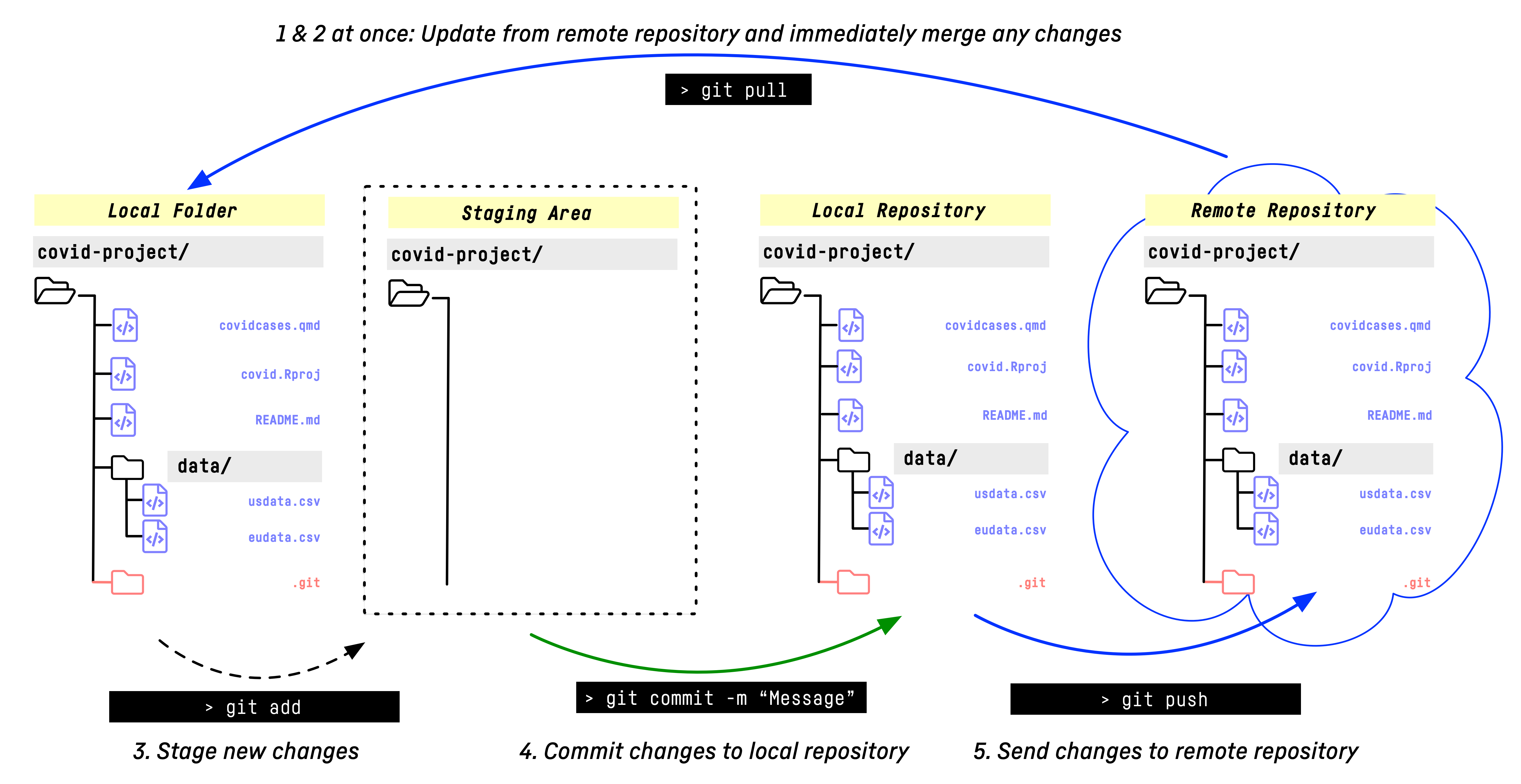

git pull

Cloning

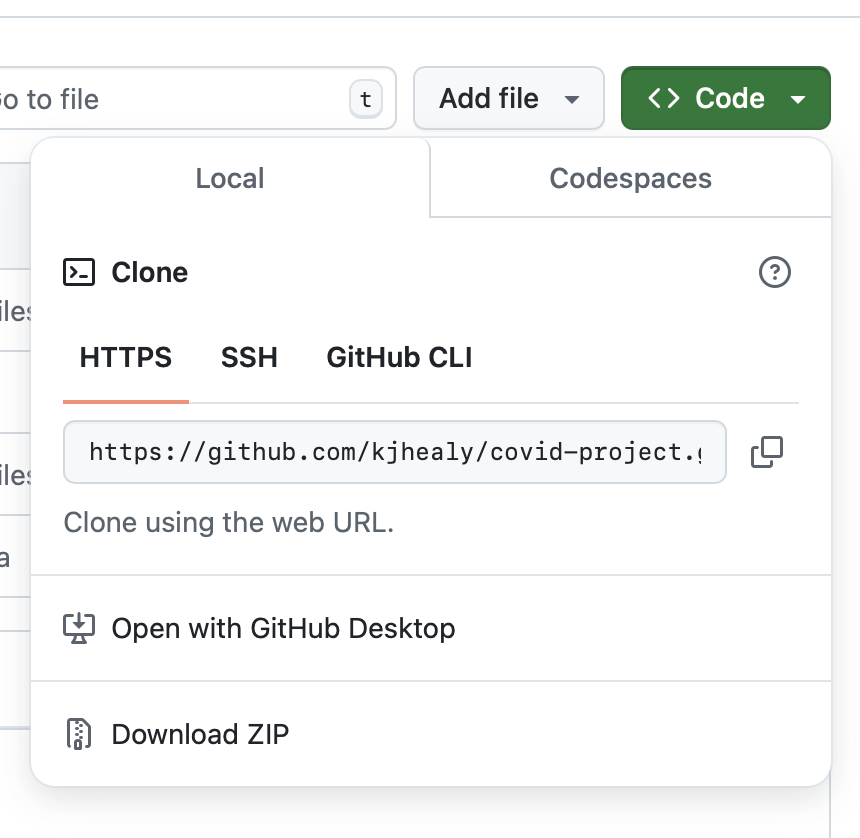

Cloning a Repo

What if you want to work with someone else’s project?

Toy Covid Project on GitHub

Cloning a Repo

- You can use git or a git client to clone via HTTPS or SSH

- HTTPS + a PAT token is easiest

- There’s also the

ghcommand line tool, which is for usinggitspecifically with GitHub

Cloning a Repo

git clone puts the repo in your current folder.

❯ cd Documents/data/

❯ git clone https://github.com/kjhealy/covid-project.git

Cloning into 'covid-project'...

remote: Enumerating objects: 23, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (23/23), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (15/15), done.

remote: Total 23 (delta 8), reused 22 (delta 7), pack-reused 0 (from 0)

Receiving objects: 100% (23/23), 577.21 KiB | 5.77 MiB/s, done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (8/8), done.

❯ cd covid-project/

❯ ls

README.md covid.Rproj covidcases.qmd dataCloning a Repo

Now you have access to the full history and any branches, etc.

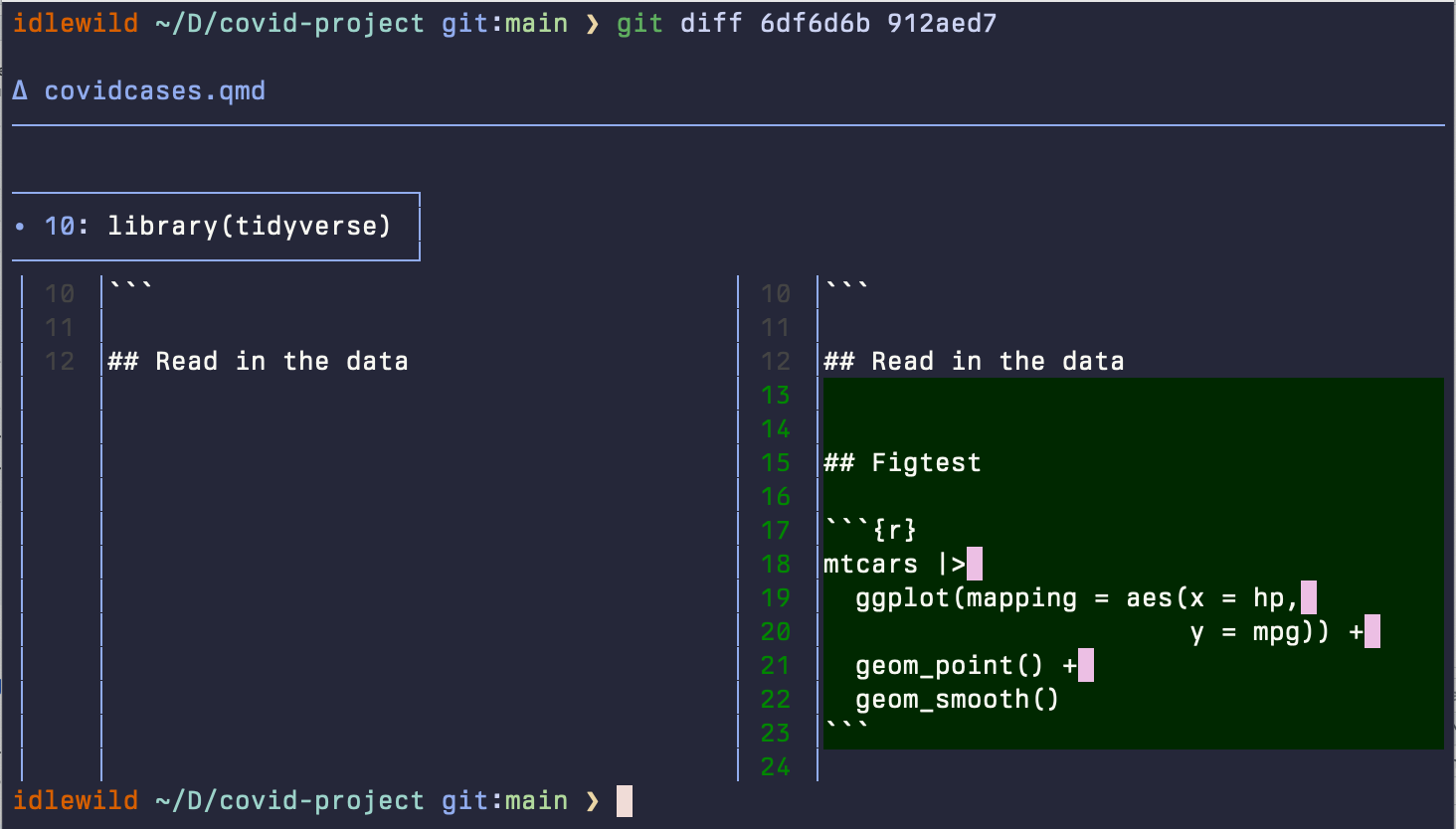

Checking Changes

Use git diff to compare your working folder with the most recent commit (the default), or to compare changes between two commits.

Project State

Here’s the state of this course’s project as I write this:

idlewild ~/D/c/mptc git:main ❯ git status

On branch main

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/main' by 1 commit.

(use "git push" to publish your local commits)

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: slides/05-slides.qmd

modified: slides/06-slides.qmd

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

assets/04-git/04-github-clone.png

assets/04-git/04-github-covidproject.png

data/dfstrat.csv

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Branches

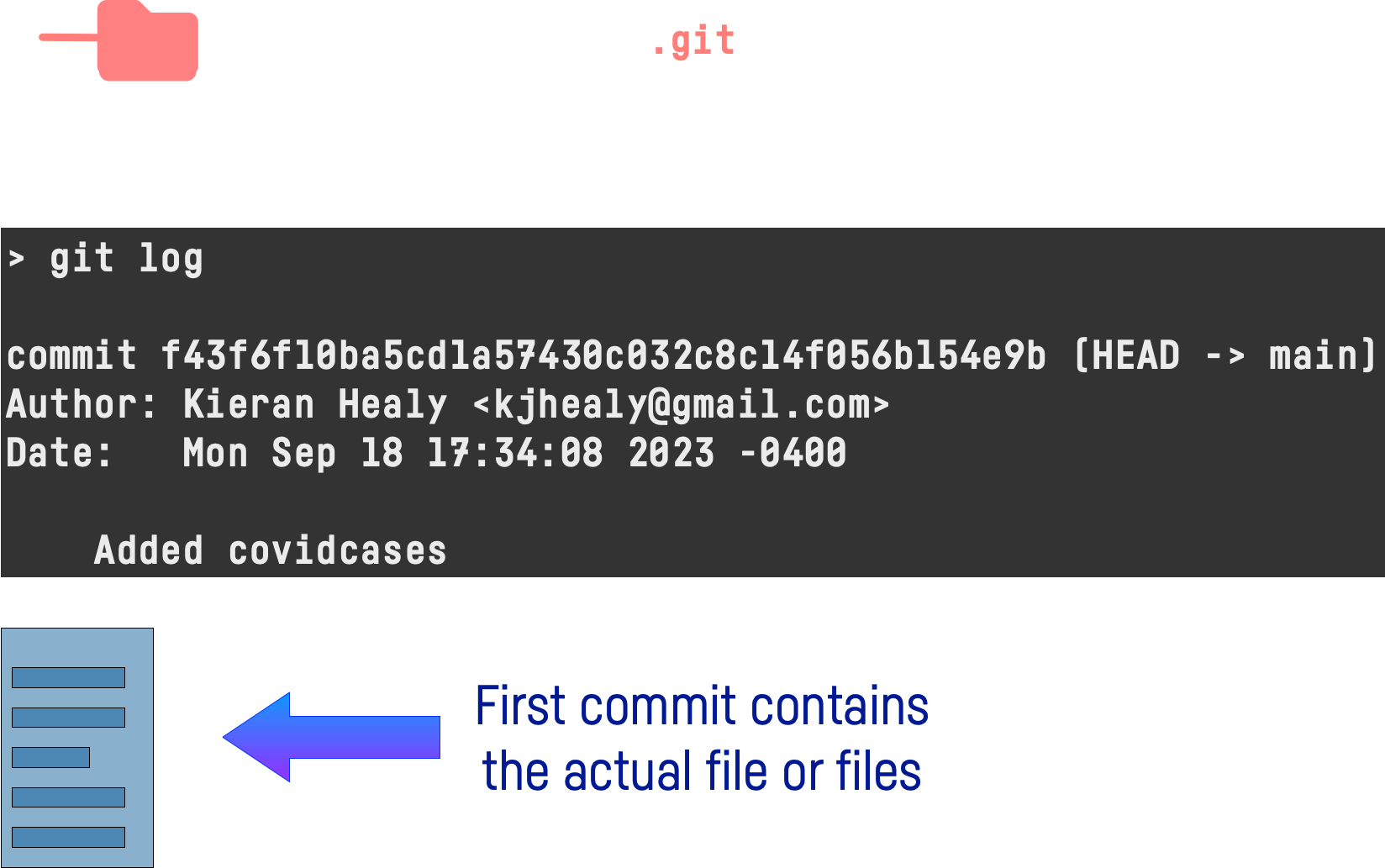

Our project again

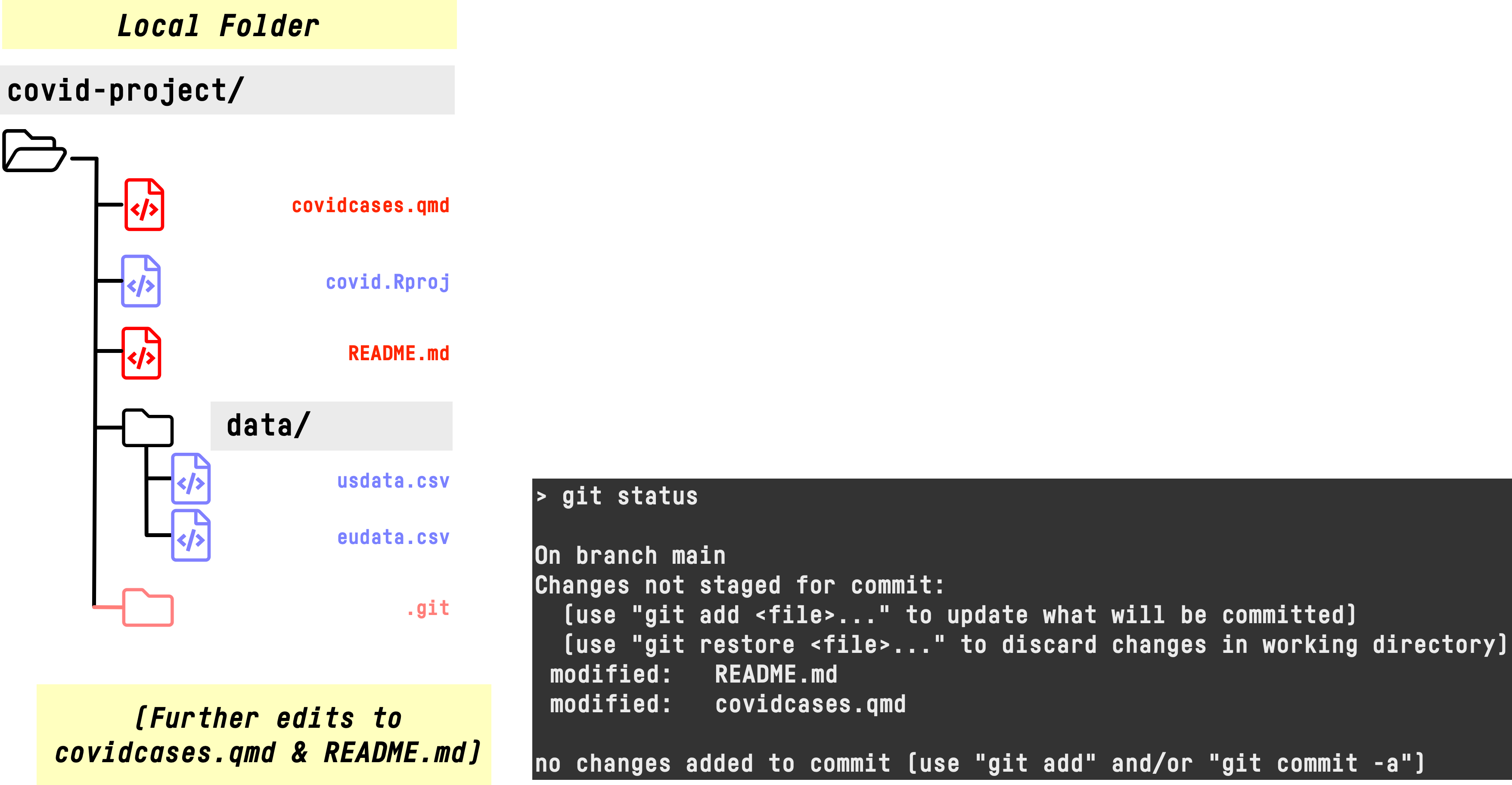

❯ git log

commit 6df6d6b10b127e87115dceac06c869150b67e800 (HEAD -> main, origin/main)

Author: Kieran Healy <kjhealy@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Sep 18 17:49:33 2023 -0400

Began writeup

commit ef0772106fe4d6f10ee62afd3c951ff14b16efb1

Author: Kieran Healy <kjhealy@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Sep 18 17:38:55 2023 -0400

Data and Rproj files

commit f43f6f10ba5cd1a57430c032c8c14f056b154e9b

Author: Kieran Healy <kjhealy@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Sep 18 17:34:08 2023 -0400

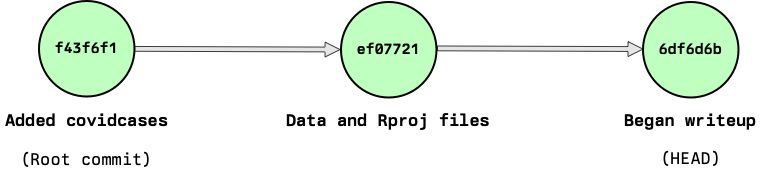

Added covidcasesOur project again

- Individual commits can be referenced by their

SHAhash. - Usually the first few bits are sufficient to ID the commit in a single project.

> git log --oneline

6df6d6b (HEAD -> main, origin/main) Began writeup

ef07721 Data and Rproj files

f43f6f1 Added covidcases- The current commit is called the

HEAD

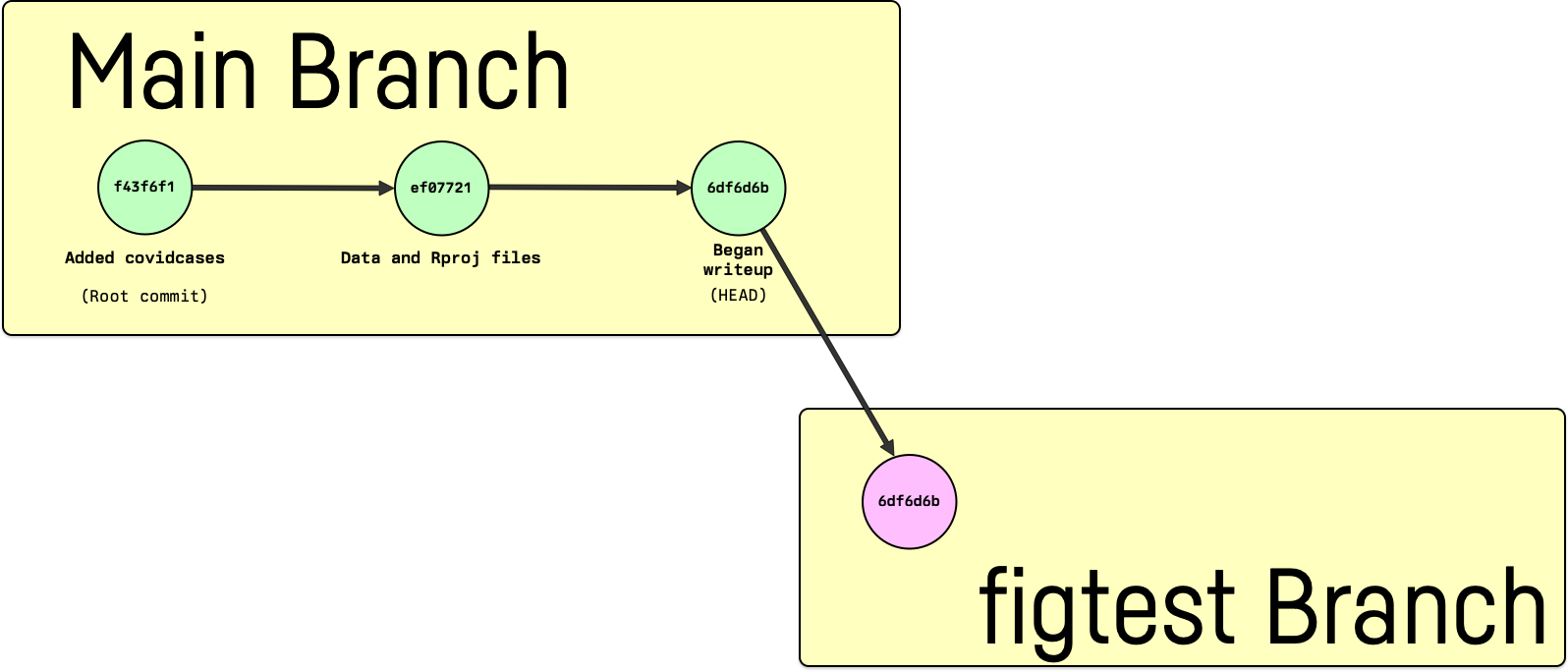

Our project again

- The SHA or commit id always refers to the same code.

- Zooming out from the various files changed in each case to the level of commits, our project looks like this:

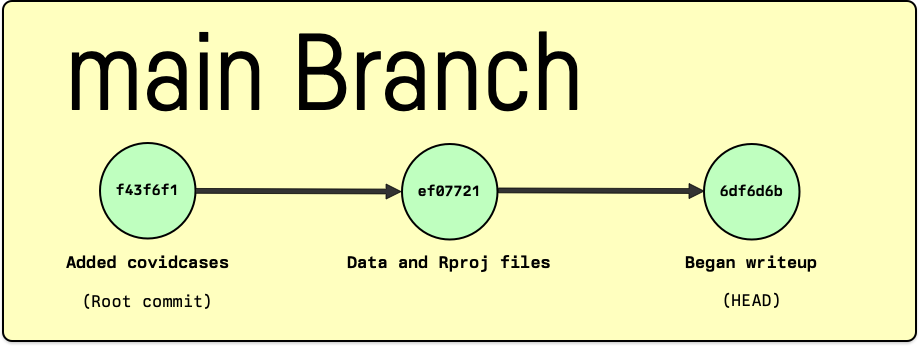

We’re on a branch

- By default we’re on the

mainbranch

We can create branches

We make some edits in covidcases.qmd

What’s our status?

# Back at the shell here

> git status

On branch figtest

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: covidcases.qmd

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Commit changes on the new branch

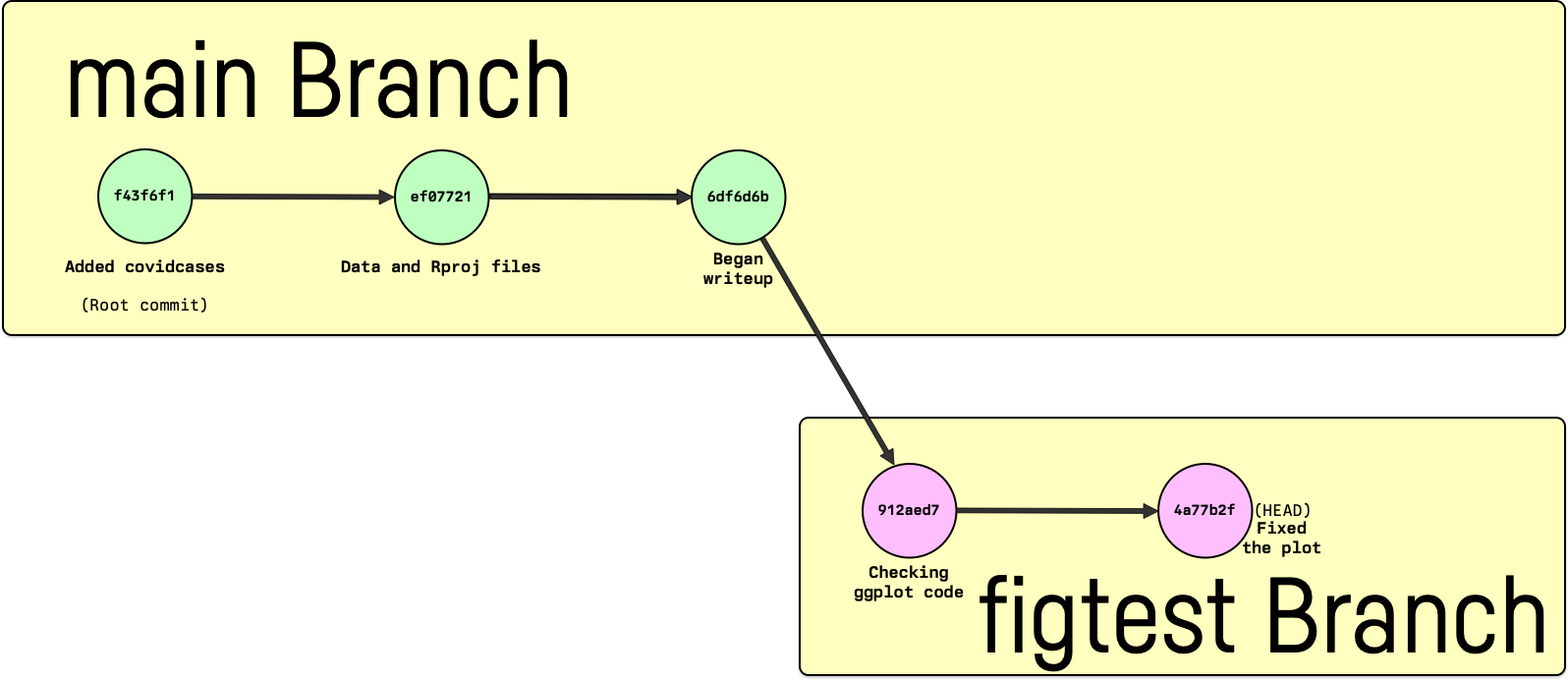

Schematically

Look at the whole log

> git log --abbrev-commit

commit 912aed7 (HEAD -> figtest)

Author: Kieran Healy <kjhealy@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Sep 18 20:25:42 2023 -0400

Checking ggplot code

commit 6df6d6b (origin/main, main)

Author: Kieran Healy <kjhealy@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Sep 18 17:49:33 2023 -0400

Began writeup

commit ef07721

Author: Kieran Healy <kjhealy@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Sep 18 17:38:55 2023 -0400

Data and Rproj files

commit f43f6f1

Author: Kieran Healy <kjhealy@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Sep 18 17:34:08 2023 -0400

Added covidcasesStatus?

Make some more changes …

Schematically

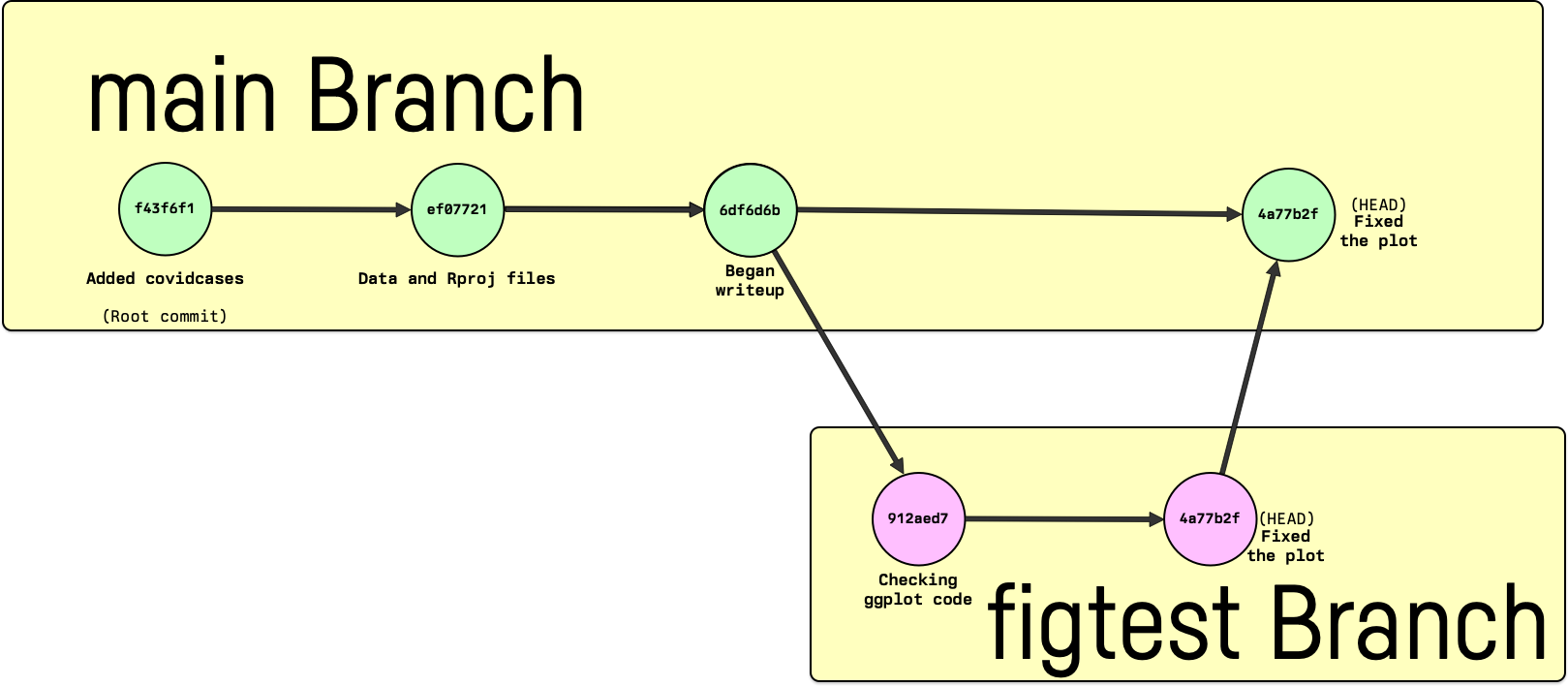

Merge it back in to main

- None of the code we wrote in the last two commits is on this branch.

> git merge figtest

Updating 6df6d6b..4a77b2f

Fast-forward

covidcases.qmd | 13 +++++++++++++

1 file changed, 13 insertions(+)- And now it is.

Schematically

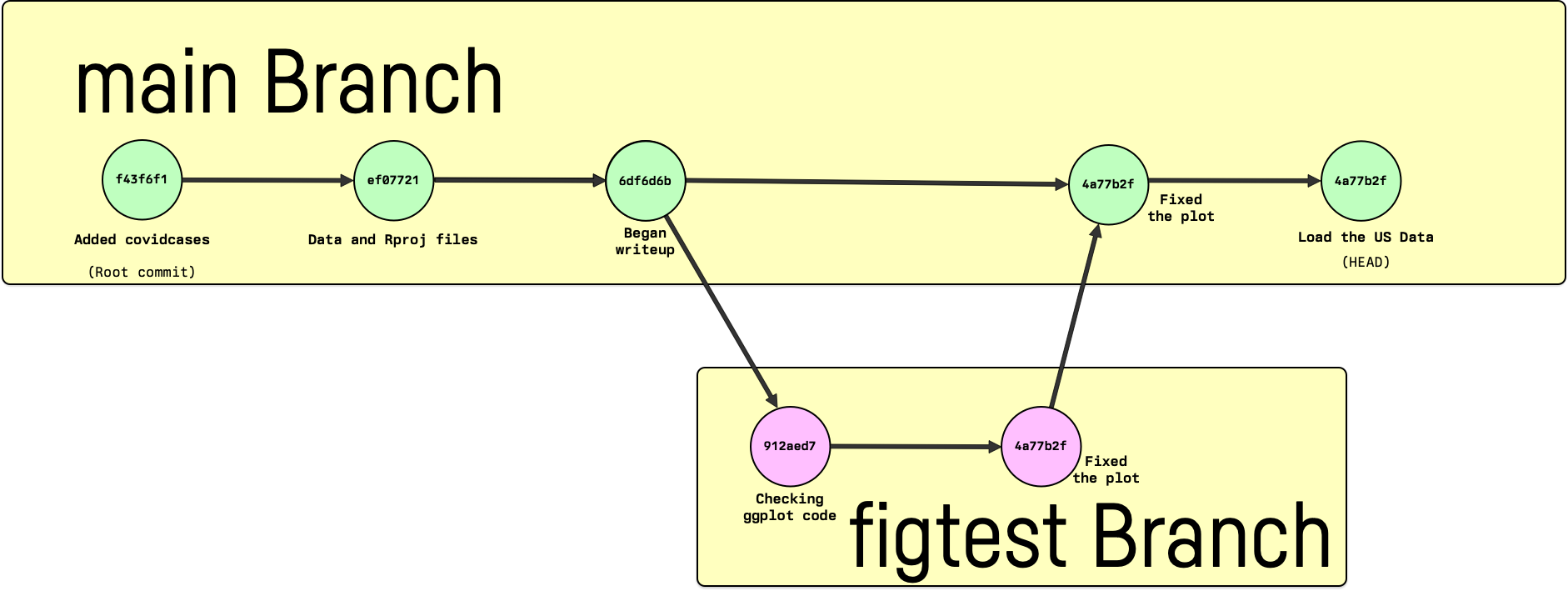

Write some more

- Make some more edits and commit those changes.

Schematically

Where are we?

> git log --abbrev-comit

commit 06677f4 (HEAD -> main, origin/main)

Author: Kieran Healy <kjhealy@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Sep 18 20:45:10 2023 -0400

Load the US data

commit 4a77b2f (origin/figtest, figtest)

Author: Kieran Healy <kjhealy@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Sep 18 20:33:57 2023 -0400

Fixed the plot

commit 912aed7

Author: Kieran Healy <kjhealy@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Sep 18 20:25:42 2023 -0400

Checking ggplot code

commit 6df6d6b

Author: Kieran Healy <kjhealy@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Sep 18 17:49:33 2023 -0400

Began writeupSummary

It’s a log book

- For single person projects you can go a long way with a very basic git workflow.

- Essentially do your work then

add,commit, andpushthe results. - At a minimum you will be left with a record of your project’s development where you can revist any commit and see what the state of the project was at that point.

It’s a testbed

- A little discipline with branching will let you experiment with new lines of work or code without getting lost or losing the ability to revert to what was there before, all in the same project folder.

- Successful lines of inquiry can be merged into the main branch, unsuccessful ones kept for the record or discarded altogether.

It’s a collaboration tool

- The combination of multiple copies of the repository on the one hand and the act of branching and merging on the other generalizes to working with multiple contributors to a repository and managing all of their work.

- Again, Git requires a bit of discipline about this—a team should have rules about branch naming, task prioritization, bug fix procedures, etc.

- Services like GitHub provide most of their value by offering ways to manage these tasks in the context of a git-based way of working.

It’s often a pain

- Underneath Git is kind of a mess.

- Various design features make it easy to be confused or misled.

- Start with the Sylor-Miller & Evans zine.